Still feeling that August is the new October, although that particular day happened to reach over ninety degrees, I watched Halloween. Not the John Carpenter original; I’ve seen that one a few times before. No, I watched the 2018 version only to learn it’s a retcon. If you’re like me you’ll wonder what a retcon is. It’s a portmanteau of “retroactive continuity.” That’s where a sequel goes back and makes adjustments, or simply ignores, story elements from the original to take the story forward. I haven’t followed the Halloween franchise. There are too many movies I want to see that are original, with fresh ideas, to be spending my time trying to find my way through an emerging mythology of a serial killer. Michael Myers, as horror fans know, inexplicably killed his sister as a child. As an adult he terrorized Haddonfield, Illinois one Halloween and Laurie Strode was the final girl.

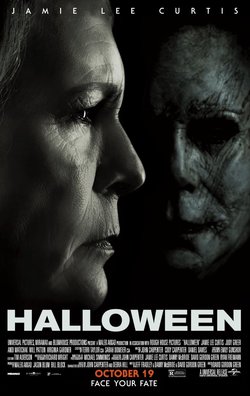

What drew me to this sequel was that Jamie Lee Curtis was back as Strode, all grown up. Michael predictably escapes again and goes for an even higher body count in Haddonfield. Laurie, meanwhile, has gone NRA and booby-trapped her entire house in anticipation of this day. You can see the draw, I hope. You kind of want to see how this ends. The original had Michael’s apparently dead body disappear at the end. In the retcon he was arrested after that and re-institutionalized. The thing is, you can never really kill a monster. Original scenes and scenarios are revisited, and those familiar with the Carpenter story are rewarded by situations that subvert expectations. Where is he hiding this time? You always watch the credits roll wondering how “the authorities” don’t realize that a guy shot, stabbed, and incinerated and keeps coming back might be something other than human to be put in an asylum.

I should know better than to watch these kinds of movies when I’m home alone, but I don’t. So it’s a good thing that I try to piece all these things together. We have three strong women—three generations of final girls here, and the obligatory basis for a sequel. (At least two, in fact, bringing the franchise up to thirteen movies.) Laurie’s granddaughter is among the virginal, non-drinking final-girl prototypes. Her less Puritan friends are killed off, although her worthless boyfriend survives the night. You’ve got to love the endless self-references of such situations. That’s why we keep on coming back. We’ve seen it before but we still want more. Even if it’s only August.