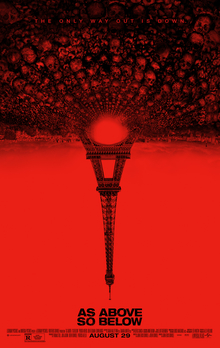

Indiana Jones in National Treasure, in found-footage horror format. That’s the feel of As Above, So Below. Only Jones is a woman. There’s plenty of religious imagery in this movie, but the story’s not that great. One of the reasons is that it’s too difficult to swallow, although it does score serious points on the claustrophobia scale. At the beginning I wondered if I was going to make it through since Dr. Dr. Scarlett Marlowe’s cell phone is constantly moving as she continues her father’s search for the philosopher’s stone. Surviving the situation in Iran, the remainder of the film takes place in Paris, especially the catacombs. My level of impressedness went up when I learned that the movie really was shot in the catacombs. Unfortunately it didn’t really help the story.

Alchemy, as part of esoterica, is purposefully difficult to understand. Marlowe is continuing her dead father’s search for the philosopher’s stone that can change things into gold. Her friend George (who repairs the clockwork for the bells at Notre Dame) is forced into the catacombs with her and her cameraman Benji. They’re led by three Parisian cataphiles and some shots look like they were lifted directly from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, including the use of her father’s notebook. Instead, the group enters the gates of Hell. There are lots of scary things down there, many of them unexplained. Some reflection reveals that they are all having to confront their pasts—or at least some of them are. One of the cataphiles is killed before we learn her secrets. And one of the survivors has no real backstory. Six go in and three come out.

The movie plays with some interesting ideas, but it’s hard to swallow that an actual bona fide archaeologist would go on an illegal treasure hunt. And that she knows of a secret chamber in the catacombs that has remained undetected by specialists. I began scratching my head. And when the group (or some of them, anyway) begin finding artifacts from their personal pasts in the catacombs, credibility is strained even further. The idea that it’s important to come to terms with your past is a good one. But once the young people begin dying and the rest have to keep going deeper and deeper to get out, the illusion is broken by Marlowe just dashing back to get a different stone to save George. If it were just a matter of popping back, wouldn’t they have tried that earlier? There are some Bible quotes, making this a candidate for the also unlikely Holy Sequel.