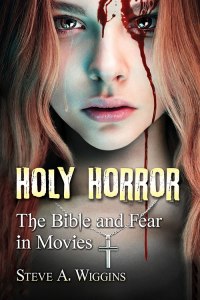

It’s not that the delay is actually horrible. Horror movies, after all, come into their own with the darkening days of fall. Nevertheless it occurred to me that now August is about to exit stage left, some may be wondering where Holy Horror is. After all, the website originally said “August.” The truth is nobody really understands the mysteries of the publishing industry. Like so many human enterprises, it is larger than any single person can control or even comprehend. I work in publishing, but if I were to subdivide that I’d have to say I work in academic publishing. Further subdivided, non-textbook academic publishing. Even further, humanities non-textbook academic publishing. Even even further, religion—you get the picture. I only know the presses I know.

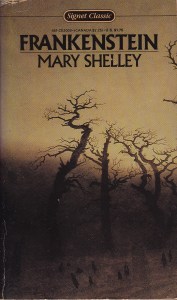

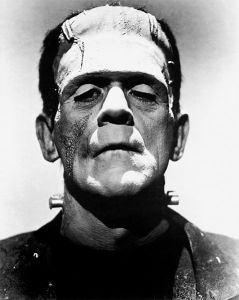

It suits me fine if Holy Horror gets an autumn release. I don’t know, however, when that might be. I haven’t seen the proofs yet, so it’s hard to guess. Appropriate in its own way for horror. The genre deals with the unexpected. Things happen that the protagonists didn’t see coming. In that respect, it’s quite a bit like life. My work on Nightmares with the Bible is well underway. When you don’t have an academic post your research style necessarily changes, but I’m pleased to find that books can still be written even with the prison walls of nine-to-five surrounding one. It may be a bit like Frankenstein’s monster (happy birthday, by the way!), but it will get there eventually.

Of my published books so far, Holy Horror was the most fun to write. It wasn’t intended as an academic book, but without an internet platform you won’t get an agent, so academic it is. It’s quite readable, believe me. I sometimes felt like Victor Frankenstein in the process. Pulling bits and pieces from here and there, sewing them together with personal experience and many hours watching movies in the dark, it was horrorshow, if you’ll pardon my Nadsat. We’re all droogs, here, right? I do hope Holy Horror gets published this year. Frankenstein hit the shelves two centuries ago in 1818. Horror has been maturing ever since. So, there’s been a delay. Frankenstein wasn’t stitched up in a day, as they say. And like that creature, once the creator is done with it, she or he loses control. It takes on a life of its own. We’ll have to wait to see what’s lurking in the darkening days ahead.