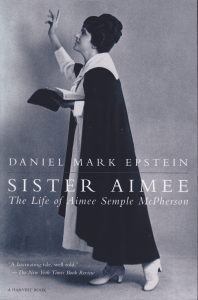

It was kind of a game. A game to teach us about important people, living or dead. The fact that we were playing it in high school history class, taught by one of my favorite teachers, made it even better. Everyone wrote a name on an index card—a person in the news or somebody from American history in the past. A student sat facing the class while the teacher selected a card and held it over the student’s head, so we could all read who it was, all except the chosen one. Then s/he would ask questions to guess whose name was written. I remember very well when the teacher picked up my card and read it. He said “that’s really a good choice!” The name led to a bit of joshing. “Is he alive or dead?” the student asked. “How can you tell?” joked our teacher. It was the one name the selected student couldn’t pin down, no matter how many questions she asked.

It’s fair to say that Billy Graham had a profound influence in my life. As a curious—and very frightened—child, whenever his crusades were on television I would watch, transfixed. I responded to his altar calls at home. Multiple times. My emotions were overwrought and I’d awake the next day feeling redeemed, for a while. I had no real mentors in my Fundamentalism. Ministers preached, but they didn’t explain things. Not to children (what was Sunday School for, after all?). All I knew was that when the rhetoric reached Hell, and the possibility I would die that very night, repentance seemed like the only logical option. The reality of the choice—a black and white one, no less—could not be denied. Either you were or you weren’t.

As my point of view eventually shifted around to that of my high school teacher—I was in college at the time—I began to realize that Graham’s version of Christianity wasn’t as monolithic as it claimed to be. Once you experience other people’s experience of religion, if you’re willing to listen to them, it’s pretty hard to hold up the blackness and whiteness of any one perspective. Over the years Graham tainted his pristine image in my eyes by his political choices. His son now stands as one of Trump’s biggest supporters. Now that Billy Graham has gone to his reward, I do hope that the Almighty doesn’t hold his mistakes against him. He had no way of knowing that his sermons were terrorizing a little boy in western Pennsylvania into a career track that would never pan out. Largely because other followers of Graham’s so decided. It’s kind of like a game.