The early morning sky has been putting on a beautiful, celestial waltz this week as the crescent moon, Venus and Jupiter swing close then part along the ecliptic. On such days it is easy to see how ancient people would have attributed motive and intentionality to the solar system—there’s definitely something going on up there. Then we get the images from the Mars rover Curiosity, showing us ourselves, lost in space. One of the truly iconic photographs from the last century was the earthrise taken from the moon. Until that moment it was difficult to conceive that we really were spinning through space, unattached to any biblical pillars with an affixed firmament above. Now we are looking at ourselves from a distance of some 225 million kilometers, and our troubles have never seemed less significant, our god never smaller. We are the eyes in our own sky—or, more impressive yet—the eyes from some other planet’s skies. I can’t see how this would fail to have religious implications.

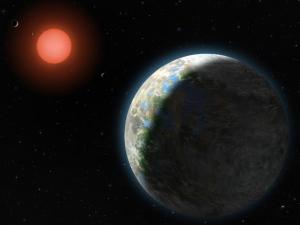

Religion often involves introspection—looking at oneself from the outside, or from another perspective. Our religious ancestors, who had no way to assess what the planets were with their conceptual framework, generally assumed them to be alive. Some cultures called them gods, others creatures, but their movement in the sky is often lost on modern people who only occasionally glance at the sky, when their smartphone is taking a little too long to download something. How sobering it is to consider that we are one of those bright dots when seen from Martian eyes. (Unfortunately I’ve been unable to confirm the stunning image that’s been circulating on the Internet claiming to be from Curiosity.) Ancient religions, by necessity, are geocentric. The earth is all they knew. Of course, religions have grown increasingly defensive as new realities have been discovered; even the Book of Mormon was written before the planet Neptune was decisively named and claimed. Changing worldviews is never easy.

Religion is often a coping mechanism to keep us grounded. Many concepts of divinity are celestially based—pointing to some divine realm in the sky. That is the perspective of an earthling. Once in space, what direction is God? We find that our up and down, near and far, are only relative terms. What the means is that increased knowledge forces further reflection on religious beliefs. We can’t stand still and let the universe revolve around us like an obsolete firmament. Religion must engage reality to remain relevant. And right now reality is rolling across the surface of Mars, looking homeward with alien eyes. How small our steeples and cathedrals look from our solar system sibling’s perspective.