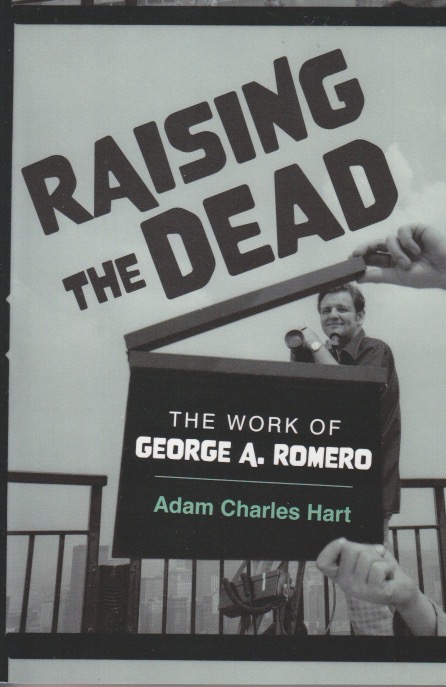

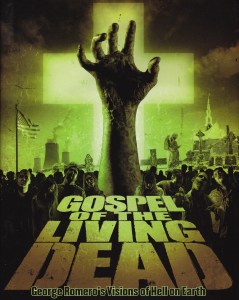

I was near fifty, if I hadn’t already passed that threshold, before I saw Night of the Living Dead. Whispered about in my high school as one of the scariest movies ever, I had avoided it. When I saw it, I immediately recognized its draw. I’ve watched several George Romero movies since then, appreciating his devotion to Pittsburgh, and to monsters. Adam Charles Hart’s Raising the Dead: The Work of George A. Romero, showed me much more than I’d ever watched. For one thing, Hart had access to the Romero archives. Although the book does spend time on the movies that Romero actually got made, it fleshes out the picture with those that remained unfilmed. Or were filmed and disappeared. And Hart also discusses the fact that Romero didn’t really think of himself as a horror auteur. He had other ideas, other projects he wanted to shoot. But he’s remembered for zombies.

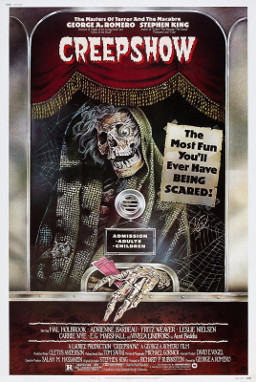

Some of this is to be expected. Although zombies had been around before, Night of the Living Dead made them into modern monsters. As much as Romero hoped the cred from that film would get him noticed, as will predictably happen in capitalism, funders wanted more of the same from him when it was noticed. Zombies went on to become a major worldwide craze. Tons of movies, long-lasting television series, zombie walks in major cities—zombies rivaled vampires for dominance among the undead. For those holding the purse strings, they were a sure thing. And those wanting to gain more lucre love a sure thing. Romero had other stories he wanted to tell, but the funders wanted more zombies.

Writers tend to have wide interests. Stephen King doesn’t only write horror. One of the more intriguing facts in this book is that Romero had even considered a remake of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” Given my particular interest in that tale, I wondered what that might’ve been like, had it ever been made. Interestingly, Hart notes that it was in a folder from 1998, the year before the Burton film Sleepy Hollow was released. (I could’ve used this information before Sleepy Hollow as American Myth went to press!) In any case, this is a fitting tribute to a guy with principles who, although he never became a director with household name recognition, managed to help change the horror genre forever. He avoided the big studios and paid the price for doing so. But he left behind a legacy, and that’s about the best that can be hoped for a writer.