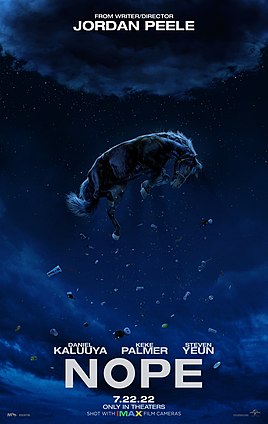

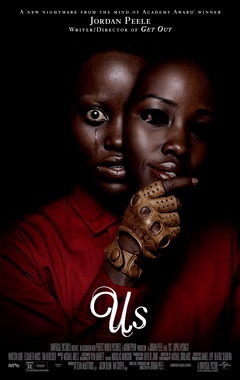

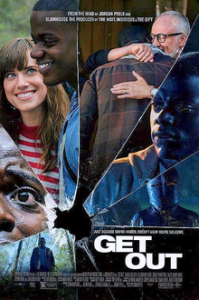

It’s perhaps this summer’s most hotly anticipated movie, but I’m not sure when I’ll get to see it. Jordan Peele’s Nope opened in theaters this weekend but I’ve been busy. For many Peele may have seemed to come out of left field with his 2017 directorial debut, Get Out (it took me a couple years to see that one), but he’d been working in films prior to that. Then Us appeared in 2019 and instantly established him as the auteur of black horror films. Like many in horror, Peele has a strong element of humor as well. His films feature black actors falling into circumstances that whites have tended to claim for themselves—being the victims of monsters (often human). I unfortunately missed Peele’s attempted reboot of The Twilight Zone in 2019-20. Nevertheless, I know he’s a kindred spirit.

I try not to watch trailers before seeing a movie. They give away too much. I don’t need any enticement to see a Peele movie. Even as I await a free weekend, I think about how horror has been a field accepting of auteurial diversity. Women have directed horror since at least the eighties. James Wan has been a major player in the genre since the early new millennium. M. Night Shyamalan had his start shortly before that. Good horror is good horror. Often such films are quite smart as well. Get Out drew attention for its social commentary—something for which Rod Serling was famous, and thus the naturalness of The Twilight Zone. But when will I have time to get out and see Nope? Perhaps I need to cash in a personal day so I can take in a matinee.

The trick will be, of course, to be on the internet without reading about it before that can happen. Taking time off work is punished with skyscrapers of emails when you return. But when I start having dreams about my boss coming to my messy house and helping me do necessary repairs, I think maybe I’ve been working too hard. Movies, in such a life, seem like superfluous luxuries. Of course, I’ve long accepted the thesis that films are our modern mythology. They are our cultural referents, and not infrequently the source of meaning. They explain our world. And they require taking at least an hour-and-a-half out of the mowing, painting, hammering, and hauling that never seem to end. Nope, I won’t have time to see the movie this weekend. Yep, I’ll be looking forward to the first opportunity to do so.