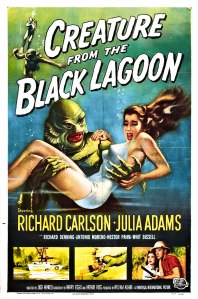

When I write fiction the genre’s difficult to define. The other thing is I tend to be behind when it comes to pop culture. It can take me years to find the time to watch a movie. This preface is an excuse for why I’ve only just seen The Shape of Water. Is it a horror movie because it features a monster? It is, of course, primarily a love story. As a parable the story has many gaps but it’s so enjoyable to watch that you don’t even mind. In the rare event that you missed the hype, it’s a tale about a woman who falls in love with a somewhat more modern version of the Gill-man. Indeed, one of the captors, Strickland, mentions finding him in the Amazon—certainly a nod toward the Black Lagoon.

There’s much you can say about a story like this, but one standout feature was that the antagonist (Strickland) frames pretty much the entire movie with the Bible. He’s not a good man, but he uses the story of Samson to keep Zelda, the Black cleaning woman, in her place. He uses her namesake Delilah (middle name) to note how she betrayed Samson. He goes on to say that God is in the image of man, either him or her. But then he adds, “Maybe a little more like me, I guess.” This gives you an idea of his character. He also notes that the creature was thought to be a god in the Amazon. At the end, as Strickland sets out to kill the creature, he again uses Samson to tell Zelda that he’s going to bring “this temple” down on all of them. That’s a healthy dose of religious imagery for a species of horror film.

The Creature from the Black Lagoon also begins with a biblical quote. And like in this movie, the real monsters are the white men who insist on destroying what’s not like them. Monsters and religion have similar pedigrees and share a number of features. A concern for those marginalized by society pervades true religion as well as monster movies. Nevertheless, the academy has trouble giving awards to any movie labelled horror. There are definitely elements of it here. It isn’t unusual to see horror defined as a movie that features a monster. This monster is a god. Interesting, how often that happens. The film’s mood, however, is also romance and a very real concern for the other. We can all learn from movies like this, even if five years late.