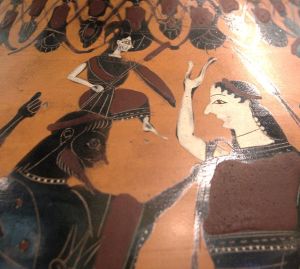

Goddesses have lately been on my mind. Both an occupational hazard and an avocation, study of the divine feminine deflects the trajectory that traditional monotheism traced and places us in the realm of the empowered female. This week my mythology class considered Athena, perhaps the truest embodiment of divinity in classical Greece. I regularly mention that in the ancient world even Plato suggests a connection between Athena and the Egyptian goddess Neith, one of the most ancient of the gods of Lower Egypt. When a friend coincidentally emailed a question about Neith, I realized the goddess was calling out for a blog post.

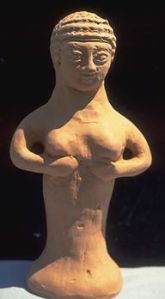

Neith is difficult to define partially because of the nature of Egyptian religion and its evidence, but also because of her great antiquity. She is a predynastic goddess, dating from before the founding of a united Egypt (back in the days when Egypt was united). She is represented by symbols of both weaponry and weaving (thus associated with Athena), and since she is so ancient, she became a creator. She is occasionally regarded as the mother of the gods. A question that naturally arises for all creators is from whence did they come – the classic chicken-or-the-egg conundrum. Mythology offers a number of options for self-generation, but most often creator gods simply bring themselves into being without many details being supplied. After all, no one was there to witness the miracle of the first birth.

Neith is difficult to define partially because of the nature of Egyptian religion and its evidence, but also because of her great antiquity. She is a predynastic goddess, dating from before the founding of a united Egypt (back in the days when Egypt was united). She is represented by symbols of both weaponry and weaving (thus associated with Athena), and since she is so ancient, she became a creator. She is occasionally regarded as the mother of the gods. A question that naturally arises for all creators is from whence did they come – the classic chicken-or-the-egg conundrum. Mythology offers a number of options for self-generation, but most often creator gods simply bring themselves into being without many details being supplied. After all, no one was there to witness the miracle of the first birth.

Like most Egyptian creator gods, Neith represented preexistence and creation. She is occasionally androgynous – a necessary precondition for being an initial creator – and is said, by Proclus to have claimed, “I am all that has been and is and will be.” In short, nobody knows where she originated. Like many pre-biblical gods, Neith practices creation by speaking aspects of the world into existence, a technique called creation by divine fiat. This is something that Yahweh will later borrow in Israel. Although the Egyptian myths do not directly address the coming into being of Neith, she represents what every observer of nature knows: monotheism loses an essential element when it supplants one gender instead of embracing both.