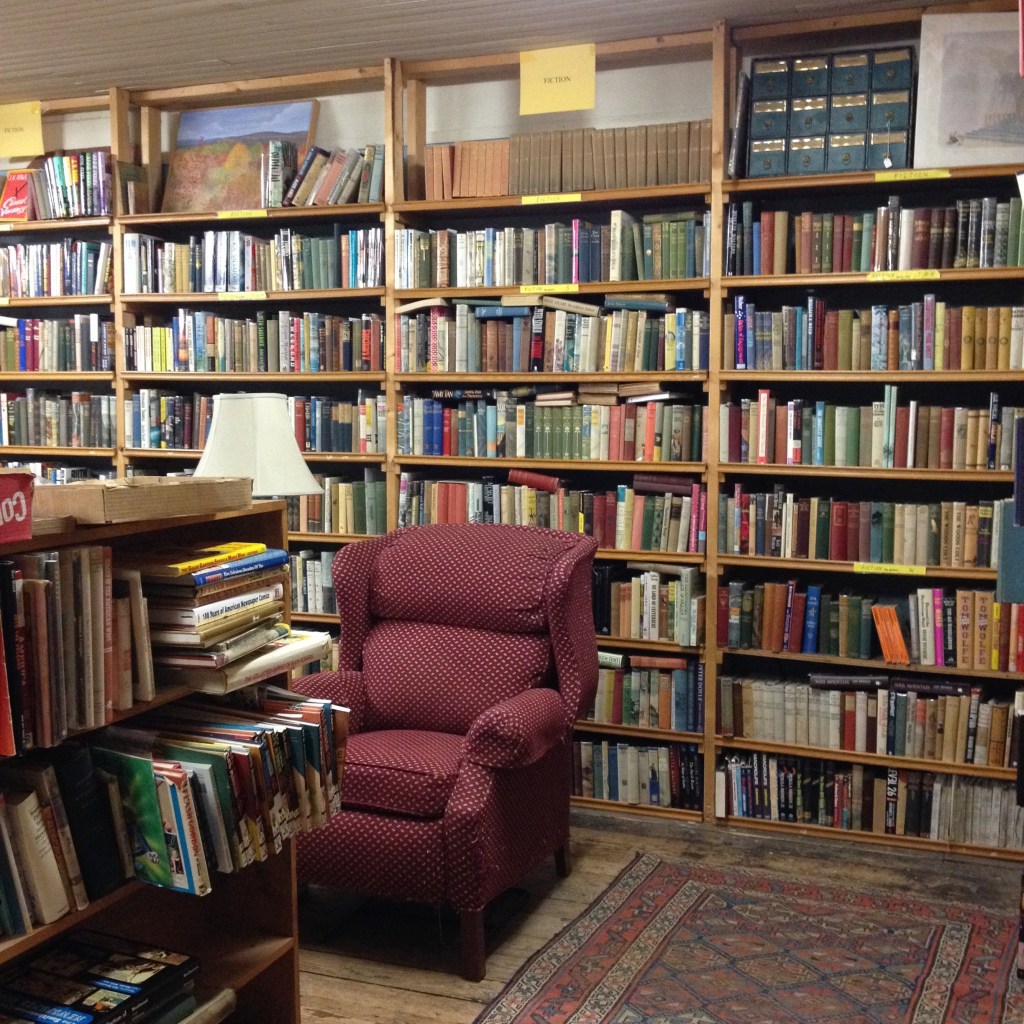

Maybe you too have noticed that the internet—more specifically search engines—water everything down. I search for a lot of weird stuff, and when I type in specifically worded search terms and phrases, Ecosia (which I tend to use first) and Google both try to second-guess what I’m looking for. Also, they try to sell me things I don’t want along the way. It’s no surprise that the web was commercialized (what isn’t?) but it does make it difficult to find obscure things. I don’t pretend to know how search algorithms work. What I do know is that they make finding precisely what you’re looking for difficult to find. Even when you add more and more precise words to the search bar. Tech companies think they know what you want better than you do. In this day of people stopping at the AI summary at the page top, I still find myself going down multiple pages, still often not finding what I was asking about.

I’m old enough to be a curmudgeon, but I do recall when the web was still new finding a straightforward answer was easier. Of course, there are over 50 billion web pages out there. Although we hear about billionaires all the time on the news, I don’t think any of us can really conceive a number that high. Or sort through them, looking for that needle in a haystack, from Pluto. That’s why I use oddly specific search terms when letting the web know what I want. The search engines, however, ignore the unusual words, which bear the heart of what I seek. They wash it out. “Oh, he must want to buy breakfast cereal,” it seems to reason. “Or a new car.”

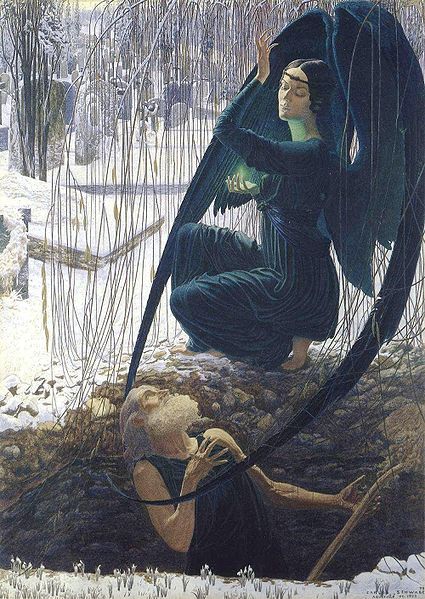

Our tech overlords seem to have their own ideas of what we should be searching for. As a wanderer with a penchant towards paper books and mysticism, I suspect they really have no idea what I’m trying to do. Mainly it is to find exactly what I’m typing in. They often ask me “did you mean…?” No. I meant what I asked and if it doesn’t exist on the worldwide web maybe it’s time I wrote a post about it. It may take the web-crawlers and spiders quite some time to find it, I know. 50 billion is a lot of pages to keep track of. Some of my unusual posts here are because I can’t find the answer online. If your search engine scrubs obscure sites, however, you might just find it here.