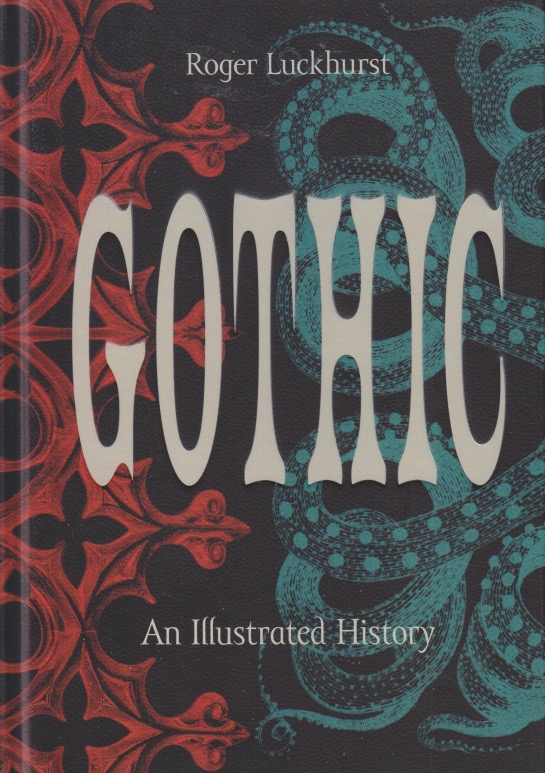

I love this book. Roger Luckhurst understands that the gateway to horror is the gothic. In Gothic: An Illustrated History he offers a world-wide, luxuriantly illustrated tour of both classic and contemporary gothic. As a category, it’s difficult to diagram precisely. Luckhurst does it through a series of themes: architecture and also form, various landscape settings, how the four cardinal directions appear in the gothic imagination, and, of course, monsters. Each of these themes is divided into four or five chapters. Not wanting to rush, I limited myself to a chapter a day, but I’m sure I’ll be dipping back in again. This is the kind of book that both gives you ideas of new books to read and movies to watch, and affirms the choices that you’ve already made in those regards. In other words, this is a place horror fans would naturally feel at home.

The gothic entered my life at a young age, partially because I was living it (unwittingly) but mostly because it appealed to me. It made me feel good watching monster movies and Dark Shadows with my brothers, and later, reading gothic novels. There’s definitely a nostalgia to it. I loved gothic architecture from the moment I first saw it. Not that Franklin had soaring cathedrals, but there were some very nice Victorian houses in town. And when I saw cathedrals I felt a strange stab of joy. Although I sublimated my love of gothic while working on my academic credentials, I couldn’t stay away from ruined castles and abbeys in Scotland. Although I was trying to be a scholar, I knew what secretly inspired me was made of coal-blackened stone. Even if I didn’t say it aloud, the monsters of my imagination lurked there.

The narrative accompanying the wealth of images in this book probes what makes gothic tick. It would be impossible to cover it all in one tome, of course. My current fascination is with dark academia (an aspect perhaps too new to be in Luckhurst). Dark academia’s draw is that it revels in the gothic, placing it in educational settings. But it can occur anywhere, as Luckhurst clearly shows. Anywhere that there might be shadows or reflections. Anywhere that experiences nightfall and autumn. Anywhere people must face their fears. While my usual avocations always please me, when I see the gothic addressed directly it takes my breath away. No doubt, mine has been a strange life. One in which, even before I reached my first decade, I found the gothic vital and necessary to an odd kind of happiness. This book brings it clearly into focus.