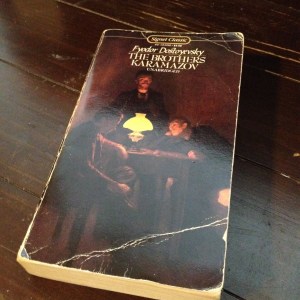

So, after writing a post about The X-Files, I finished season three, forgetting up until then that the last episode was “Talitha Cumi.” Apart from being part of the alien mythology arc, the biblically literate recognize the title as the words Jesus said to Jairus’ daughter as he raised her from the dead. Appropriately enough, the episode features an alien-human hybrid that is able to raise the dead and to shape-shift. This particular episode also has an intriguing dialogue between the Smoking Man and Jeremiah Smith (the hybrid) where they discuss whether the alien agenda for people, or that of the shadowy cabal, is better. With a theology drawn from the Grand Inquisitor chapter of The Brothers Karamazov (according to Wikipedia, and which I have no reason to doubt), they argue from different perspectives. The Smoking Man explains that they have given people science instead of God and miracles will only confuse the issue.

While not exactly Fyodor Dostoyevsky, this scene raises some very real questions. Are people happier not believing? Not only that, but the cynicism of the Smoking Man matches rather precisely the modus operandi of our government some two decades later. There’s a reason we keep coming back to the classics. The X-Files mythology is, like the Cthulhu Mythos, woven throughout a larger tapestry whose warp and weft both seem to be religion. It ran far longer than Sleepy Hollow ever did, and it would take considerable effort to tease all of the Bible, let alone religion, out of it. They make the story far more believable.

This particular episode also displays the staying power of the classics. Long, ponderous books like The Brothers Karamazov require concerted effort to read in these soundbite days of internet hegemony. That Grand Inquisitor chapter, however, has been enormously influential. (I recall during my most recent rereading of the novel that I hit that wonderful chapter and then realized I still had hundreds of pages to go.) We often have trouble telling God from the Devil. Just look at today’s political scene and try to disagree. In the X-Files diegesis there is a shadowy, high-powered group that got to the extraterrestrials first. They keep the secrets to themselves while the masses play out their insignificant lives that enrich those in charge. Democracy, it seems, used to be about elected representatives seeing to the will of the people. It perhaps assumes a greater educational base than we’ve been able to retain. But still, with chapters like “Talitha Cumi” we see that there may be some glimmer of hope after all.