When it first appeared, mash-up literature seemed strangely novel for such a derivative art form. I read Pride and Prejudice and Zombies with some amusement, but a nagging suspicion kept asking if I was being fair to the genius of Jane Austen. At the same time, I like zombies. A lot. I decided to give the genre another try with Coleridge Cook’s mash-up of Franz Kafka’s classic, The Metamorphosis. During a long, late-evening flight from Los Angeles to New York, I finished The Meowmorphosis with a sense of dread. Instead of seeming funny, the idea of trying to make light of Kafka’s profundity felt like a devaluation to the classics of existentialist writers. Nobody writes like Kafka, Camus, and Durrenmatt any more. These are writers who welcomed me to an adulthood that seldom makes sense, but which is often generous with pain and angst.

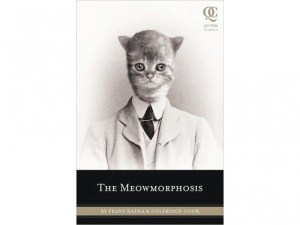

The story of The Metamorphosis is well known. In the Meowmorphosis, obviously, Gregor Samsa is transformed into a kitten and is thrown into the same dilemma. The book takes a detour into Kafka’s The Trial along the way, and my memory of The Castle is rusty enough that I may have missed if it was referenced as well. Kafka’s work passes over from the entertaining to the profound. Perhaps that is the mark of classic writers—they seldom make a career of their literary efforts, for most people who read do so for entertainment. The Metamorphosis is not easy going. Perhaps that’s why I reacted so viscerally to Kafka’s truly horrendous bug being presented as a fluffy kitten. The idea is funny, but Kafka seldom smiles.

My reaction shed some light on the concept of sacred writing. Historically, the first book to receive that accolade seems to have been the Bible. Specifically, the Torah. There are sacred writings older, I know, but the reception is what makes a book sacred, not its words. Anyone who has read the Bible knows that it is a mixed bag of profundity, tedious lists, and literary beauty. Even Fundamentalists seldom quote 1 Chronicles 1-9 with the same ardor as Genesis 1-11. It is our reception of texts that make them sacred. Perhaps Christianity was premature with its insistence on closing the canon. Some of the best literature, the most inspirational words ever to be penned, lay centuries in the future. Our world would likely be a better place if sacred texts continued to keep their borders open and would admit texts that had passed the test of time. In any honest Bible including the twentieth century, The Metamorphosis would find a place. What a world it could be.