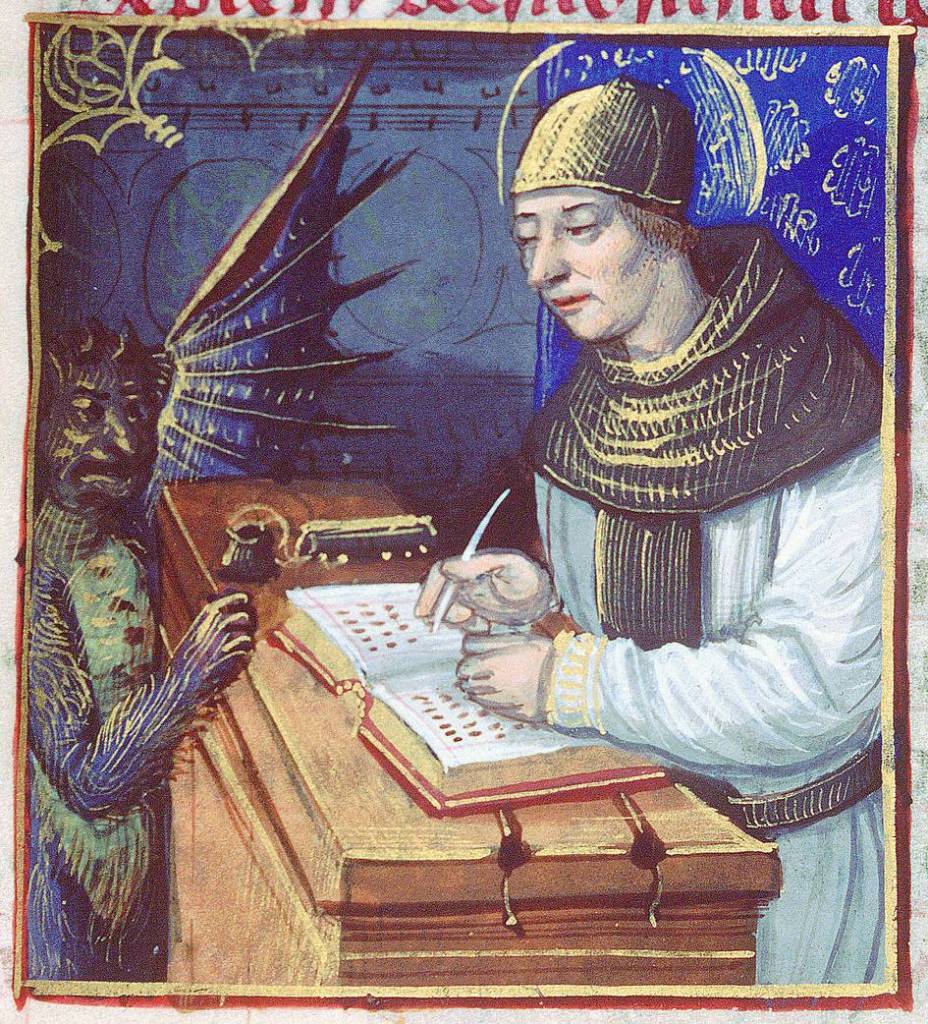

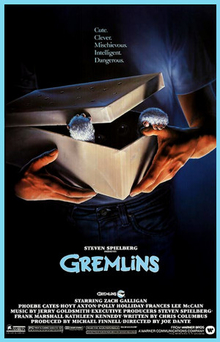

Gremlins have an ancient pedigree, whether they know it or not. Credited with airplane problems during the Second World War, these meddlers in technology had an older cousin in the demon named Titivilus. Titivilus was a demon said to be responsible for errors in the works of scribes. Long before the printing press hit Europe, manuscripts were copied by hand, of course. Anyone who works with Bibles, for example, knows that no ancient manuscript exists without errors. But scribes copied more than Bibles, and anyone who has tried to copy an entire manuscript knows that errors always creep in. (When I was a college student I tried to get my local church back home to set up a Bible-copying station so that when hungry parishioners were leaving the service they might stop and copy a verse. This was to show how errors appeared in biblical texts. The experiment took place but results were disappointing—full of errors but we didn’t get past the early chapters of Genesis).

However that may be, having a demon to blame for things going wrong proved to be mighty handy. The tradition lasted well into modern times. In the days of manual typesetting the young printers’ apprentices were called “printer’s devils.” Demons were blamed for spilled cases—capital letters were kept in the upper case, and minuscules in the lower case—and other mishaps. It may be a stretch, but such a demon interfering with humans trying to accomplish something important, led to ideas such as gremlins. Most of us, I suspect, don’t like to confess that we’re sometimes clumsy or sleepy and make errors. One of my notebooks is all crinkly because I knocked a nearly full water bottle over onto it while trying to catch a bug in my office. ’Twas no demon, just haste making waste, as it does.

The idea of someone not human to blame is compelling. All the more so because sometimes we are the legitimate victims of circumstance. Life offers many opportunities to wander, unknowingly, into situations that might not turn out so well. We don’t have minds well equipped to see the entire picture. Even if we could the universe, we’re told, is infinite. Who doesn’t make mistakes because of limited knowledge? And sometimes those mistakes can eat up years of your life. Doesn’t it seem more likely that a demon or gremlin lurks behind an all-too-human error in a judgmental world? I’m sure that, for most people, if we knew better we wouldn’t have done it. So we invent our demons. We sometimes even give them names, and thus Titivilus was born.