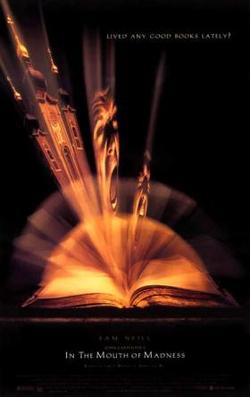

It’s been on my wishlist of movies to watch for a few years, In the Mouth of Madness. A tribute to Lovecraftian horror, as well as a probing of insanity, it is a heady mix. In keeping with my usual rules for movie watching, I hadn’t pre-read anything about it that would give away the plot. Coming to it fresh, a number of things stood out. There were some very good scenes and parts of the movie made me want to like it a lot. It is a great movie for religion and horror analysis, and in that regard it’s much better than Prince of Darkness (despite Alice Cooper). In fact, had I been able to see it years ago, it would’ve been included in Holy Horror. That itself is noteworthy since two of John Carpenter’s other movies were in it: The Fog and the aforementioned Prince. I suppose I should provide a little summary (if possible) in case you haven’t seen.

Trent is an insurance investigator, and a hardened skeptic. A horror writer who outsells Stephen King, Sutter Cane, has gone missing and Trent’s sent to investigate. He discovers that Cane is in a town that doesn’t exist (Hobb’s End) and that his books are not fiction. In fact, Trent is a character in one of his novels. When people read his latest book, In the Mouth of Madness (a title adapted from Lovecraft), they go insane and begin killing others. The plot gets a bit busy because people are starting to transform into slimy, Lovecraftian monsters and this reality, if the book is read, or movie watched, will spread to all of humanity, leading to our extinction. A bit too ambitious, the plot can’t hold all this weight, but it really isn’t bad. There’s just too much going on.

The religion elements come in because Cane has holed himself up in an unholy church. He refers to his latest novel as the “new Bible.” “More people,” he says, “believe in my work than believe in the Bible.” He later refers to himself as God. I haven’t seen all of Carpenter’s films, but there seems to be a trajectory of his earliest major films being his best. Halloween and The Thing are classics. The Fog isn’t bad. When he brings religion into his stories, as in The Fog, things begin to cloud over a bit. Prince of Darkness doesn’t deliver a believable Devil. In the Mouth of Madness doesn’t quite hang together well enough. It’s not a bad movie, though. It has given me some ideas for another book, if I can stay sane long enough to write it.