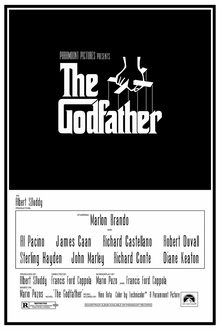

Sleep patterns often don’t fit with work patterns. The reason I wake up so early is that for years I had to do it to get to Manhattan. For work. Since ending the commuting lifestyle four years ago, I haven’t been able to adjust back to normal, whatever that may be. During a recent heatwave weekend, when it wasn’t really conducive to be doing yard work, I suggested to my wife that we watch The Godfather on Sunday afternoon. Somehow I thought it was only two hours, but it is actually much closer to three. Now this Coppola film is considered one of the greatest movies of all time and I have literally wanted to see it since 1972. There were no VCRs in those days and life has been, well, busy since college days.

It is a powerful movie, even today. I knew the basic plot and I started to read (I can’t recall if I finished it) the novel in the early seventies. All I know is that I sat engrossed as the temperatures tempted 100 degrees outside. Because I awake so early Sunday afternoons are often sleepy times for me, but I don’t nap. Napping leads to long nights and I awake early no matter what. The movie doesn’t allow for a lapse of interest. One of the scenes that had the most impact is when Michael is attending the baptism of his godson and the priest asks him if he renounces Satan intercut with scenes of his hitman killing his rival family bosses. The religious nature of the violence in the story is perhaps one of its most shocking elements, even today.

That night it was still hot, and all the water that I drank during the day made itself rather urgently felt around 2 a.m. The trick to the late night bathroom run is to keep your mind shut off. Although The Godfather ended nearly twelve hours earlier, it crept back into my head, keeping me awake after that. Of course, I had a full day of work—there are no allowances for aging in this thing of ours called capitalism—ahead. The thing is, when else do we find three consecutive hours to catch up with a cultural landmark but a Sunday afternoon? Are you supposed to take a vacation day to do it? I have no regrets about having watched the movie—it was like an offer I couldn’t refuse. It’s just the rest of life that, well, simply won’t compromise.