Being a religion specialist in a crowd of engineers is a surreal experience. Indeed, the clash of worldviews could hardly be more apparent, shy of crossing the border into Iran. I support the efforts of FIRST Robotics because they encourage children to excel in science, math, and engineering. My own childhood, however, was dominated by an overbearing religion that forever scarred me with a fear of Hell that I still can’t quite shake. Somewhere out there behind the stars there must be a horrid place engineered for the eternal torment for sinners like me, for the Bible tells me so. Speaking of stars, the live feed to kick off the FIRST Robotics Competition is sponsored by NASA. Yesterday was the international kickoff for this year’s competition, and as president of my daughter’s robotics team, I naturally sat among the well-paid engineers and professionals as we watched Dean Kamen unveil this year’s assignment.

The FIRST kickoff video is available online for those who missed the event. The organization grants millions of dollars in scholarships to deserving students, funding college careers for the future of humanity. As I watched the live feed yesterday, a profound angst settled on me. Successful guys my age working for companies flush with money described how the latest medical and humanitarian breakthroughs were being made in the sciences. I have a part-time job with no medical coverage, and know, somewhere deep inside, that if something goes seriously wrong I will be permitted to go the way of all flesh, without benefit of these great technologies. And without the benefit of spiritual reward. A lost child of the cosmos. A life spent in the pursuit of truth, yet ending up with empty hands at the end of the day.

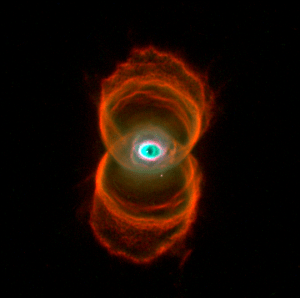

As a child I was a charter subscriber to Discover magazine. One of my earliest career ambitions was to be a scientist. One of my favorite classes in high school was physics. I was, however, haunted by the knowledge that the clergy had divined Hell behind all of this; only those who sought the keys to the kingdom would be spared. In college I majored in religion and took classes in astronomy, still flirting with my first crush. Now, an unemployed religion professor, I watch as day by day my specialization become more and more obsolete. No matter how far our telescopes peer into the universe, they just don’t spy God in an unguarded moment, captured by candid camera. Those with the money say truth lies in the progress of science, others in the unethical life of corporate America. The future lies anywhere but here in the world of religion. As I tell my students: be very careful in choosing a career. The best of intentions will lead to the worst of anxieties unless the way of the universe is truly comprehended.