I’ve obviously been reading about the Greek gods. Apart from being borrowed and renamed by the Romans they’ve remained pretty much unchanged through the millennia. Those who read a blog like this will recognize the names of many Olympians and would recognize the name of the head honcho as Zeus. The name of Zeus is Indo-European—this is a linguistic group, and not necessarily an ethnic one. That is to say, the languages of ancient India and ancient Europe are related. Zeus, it has been postulated, is related to the word Deus, familiar to many Catholics as a Latin word for God. In antiquity most gods had personal names as well as titles, but this is something we see a little more clearly in the Semitic linguistic realm. The texts of the Bible and its surrounding cultures often preserve titles as well as names.

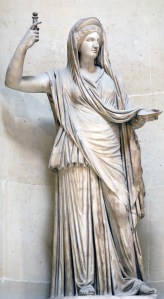

Hera is widely recognized as the consort of Zeus. It’s a bit of a misnomer to refer to divine couples as “spouses” since they really don’t comport themselves according to human-style conventions. In any case, Hera in Greek mythology is an underdeveloped character. She’s jealous of Zeus’ many affairs, and she sometimes punishes his children by other women or goddesses. Her name is a bit of a mystery, and the other day I was trying to remember where I’d read that she may be a shortened form of Asherah. My research on Asherah is now nearly old enough to fit in with the classics, but much of it still remains fresh in my mind. In any case, the reasoning went like this: Asherah always appears as the consort of the high god. The Greek Zeus was clearly influenced by Semitic ideas associated with Hadad, or Baal. And while Asherah was not Baal’s consort, Zeus is clearly the high god so his main squeeze should be that of the highest order.

Greek, as a language, had trouble beginning words with a vowel followed by the “sh” sound, like Asherah. The argument went that if you knock the “as” off the front of that divine name you’re left with Herah, and the final h isn’t pronounced anyway. This line of reasoning always made sense to me. Deities in antiquity were defined more by what they did than by what their names were. In a patriarchal world, being the consort of the highest male was about the most a goddess could aspire to. Still, we all know of the more colorful individuals who take a more forward position: Athena and Artemis—both powerful virgins—and the somewhat more naughty Aphrodite. All those names beginning with alpha! They could teach us something today, I suspect, if we read our classics.