Perhaps it’s an odd kind of nostalgia. Many people can’t wait to be done with school and get on with “life.” Some of us remain fixated at the learning stage and society used to shuffle us into colleges and universities where we could be safely ignored. One of the refrains in the very long song that is this blog has been the lack of a university library. Although I’ve tried to get to know the academics in the Lehigh Valley really only one has made an effort to befriend me and when I was asking him about library access he actually did something about it. Such acts of kindness are rare and require a kind of thinking that takes into account the circumstances of the academically othered. I’ll be forever grateful.

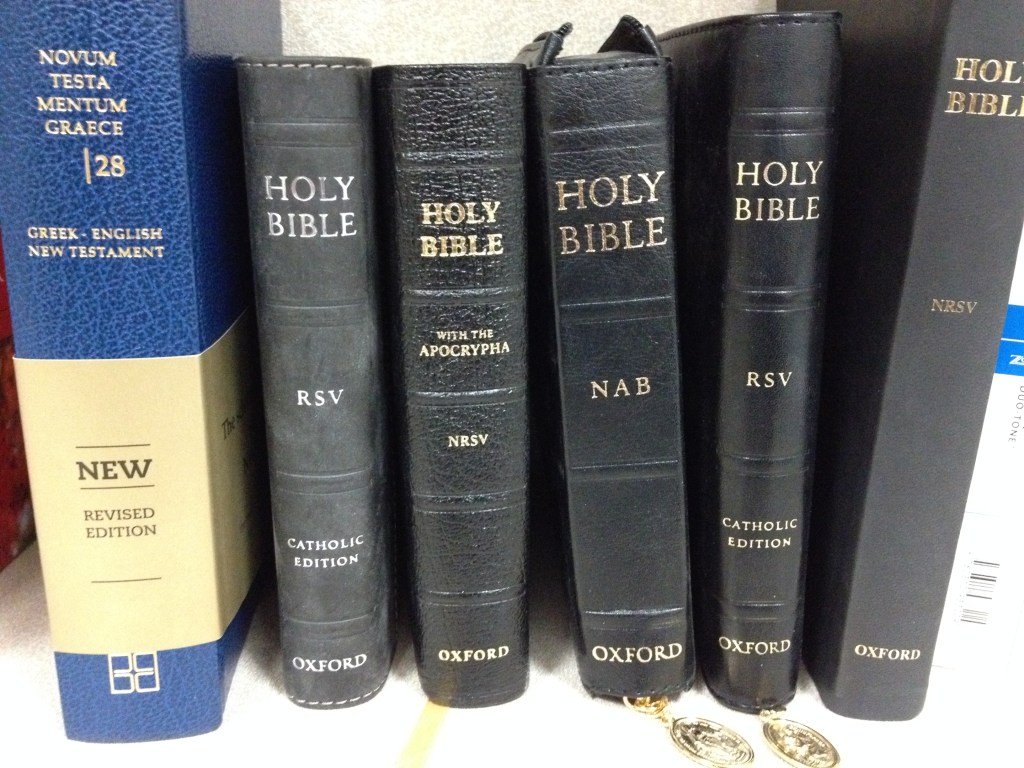

It’s been a long time since I’ve been in a college or university library. Many are protective and/or restrictive, as if knowledge is only for those academically employed. I had to look up a couple of references for an article I was writing. My colleague checked with his institution and yes, I was welcome to come in and use their collection. The night before going to campus I had a series of nightmares of various librarians barring my attempt to get to the books. I’d been trying to get there (in real life) for weeks. Between family work schedules, the occasional weekend blizzard, and the library being closed for spring break, it ended up taking about six weeks to find the time to drive there, negotiate parking, and look up the references.

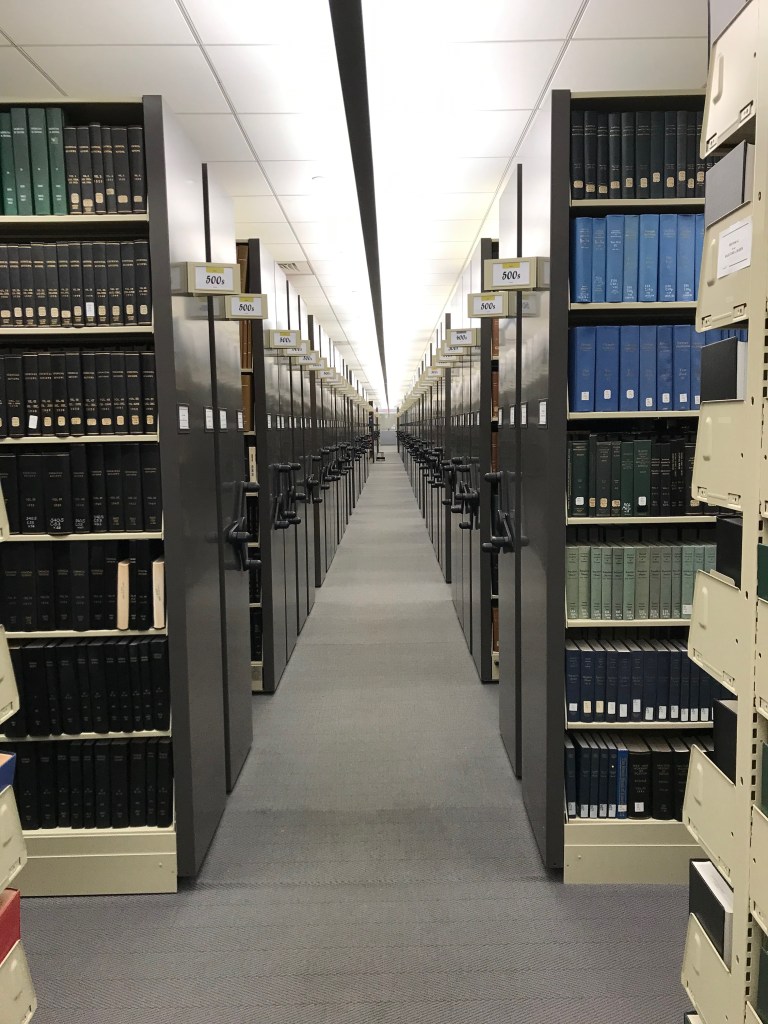

Everyone has a place they belong. Mine has unwaveringly been the college campus. It is home to me, even if it doesn’t recognize me. I’d almost forgotten the feeling of being let loose in the stacks. It was a Saturday morning and there was almost nobody else there. As early as Grove City College I cherished the feeling of spending time in the library. Few other students were hanging out there, but those of us who belong on campuses know that being surrounded by books is the only place that will ever feel like home. Having looked up my references I wished that I had more to do. I’d been to both the Dewey and the Library of Congress sections and, being a weekend, I had much else to do. Stepping back out onto campus I was filled once again with a poignant nostalgia. Getting to where you know you belong is a lengthy journey.