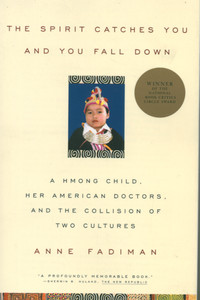

While The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, by Anne Fadiman, is not about religion, it is all about religion. The tragic story of Lia Lee is one where Hmong lives, completely immersed in what we would term “religion,” came into conflict with American perceptions of what religion should be. One of the events in Lia’s life involved the government removing her from her parents for their failure to follow doctor’s orders. Fadiman notes that this has been an issue is court cases with Christian Scientists and Jehovah’s Witnesses and other groups that refuse certain kinds of medical treatment for religious reasons. Adults may refuse—it is their constitutional right—but children cannot be subjected to an adult’s religion if it endangers their lives. Here is the rub; American religion only stretches so far. Sure, many of the faithful pray for loved ones, but they also trust the doctor’s knowledge. Not too put too fine a point on it, God doesn’t seem to do the healing unless the physician is involved. For many from traditional religions, like the Lee family, that is hardly trust at all.

Much of the problem in Lia’s case came down to taking the soul seriously. It is clear that the Hmong believe, really believe in the soul. It is the essence of a person. Reductionism declares that when all the matter is burned off, no soul remains to be found. Lia’s parents, however, could tell whether her soul was present or not just by looking in her eyes. Although she never recovered from her major seizure, the physicians had tried to prepare her parents for Lia’s immanent death. Removing her from the feeding tubes and sterile conditions of the hospital, the Lees took her home where she survived for years, although in a persistent vegetive state. Even as the book ends with Lia at seven, they are hoping for her soul to return. Lia died just two months ago, at the age of thirty. She was diagnosed as terminal at the age of four.

The story of Lia Lee is sad and one with no real villains (after the Secret War in Laos, and its aftermath). One of the most interesting aspects revolves around how the Hmong observe American religion. Well-meaning missionaries tried to convert them, but psychological studies have demonstrated that those who are the worst off are those who converted to western religions. At one point a Hmong girl, at a sacrificial ceremony to placate the spirits, tells Fadiman that she’s a Mormon. In another instance a Christian family tried to give their Hmong neighbors advice before a long drive, telling them they should pray to the Lord, not their ancestors. The Hmong honestly replied that the Lord had given him too many problems in America. It seems to me that the real issue here is just how seriously religion is taken. To the Hmong, it is their life. In capitalist America, it is very difficult to make religion your life. Even clergy have to have bank accounts, bills, and oil changes—all very secular aspects of life. If religion were taken as seriously here as among the Hmong, we would be facing a very different race this November.