Yesterday morning, like many others mesmerized by the commercialization of holidays, I had the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade on the television. I can only speak from my own experience, of course, but I know that growing up poor we used to watch this, and that my wife’s family, from different circumstances, also watched it. The friends with whom we ate our main meal watched it, and given the advertising revenues, I imagine many other people tune in every year as part of the holiday tradition. What struck me were the testimonials just before or after the commercial breaks. Celebrities shared what they liked about the holiday and many of them, unsurprisingly, focused on food. Many indicated that overeating was pleasurable. I began to think of what it means to be a nation of foodies.

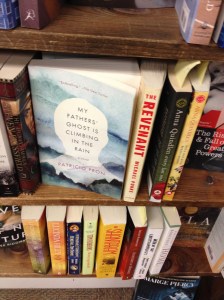

Not everyone is of a cenobitic sensibility, but focusing on the food seems to be paying more attention to the finger pointing at the moon than to the moon itself. Commercials for television shows of sweaty, nervous chefs wanting to be recognized as the best cooks in the world struck me as somewhat decadent. Like many professionals I’ve had occasion to eat in “fine restaurants” from time to time. Do I remember the food for long afterward? No. More often I recall the people I was with. What we talked about. The food, chefs may be pained to hear, was incidental. There were deeper issues afoot. If the internet’s any indication, I’m in the minority here. Foodies rule.

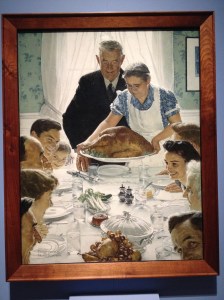

Special foods on holidays are, naturally enough, a holiday tradition. Many have their origins in the changing foodstuffs available as the seasons wend their way through their invariable cycle. Thanksgiving is like the ancient festivals of ingathering—the celebration of plenty ahead of the lean months of living on what we’ve managed to store for the season when winter reigns. Some animals cope by hibernating until food becomes available again. Others scavenge their way through chilly, snow-covered days. Gluttony, however, isn’t primarily a sin against one’s body; it’s the sin of taking more than one’s fair share. Unequal distribution of wealth is a national sin that grows worse each year. On Thanksgiving there are many people who don’t have enough to eat. Jobs can be lost through no fault of one’s own, and want can haunt late November just as readily as jouissance. Driving home we passed a shopping mall brimming with cars after darkness had fallen. The larger holiday of Black Friday had begun.