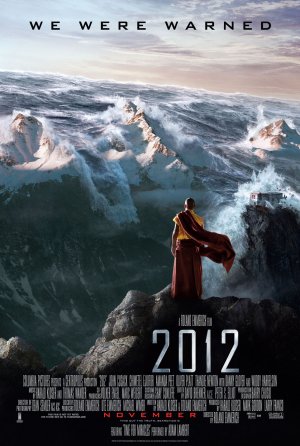

I just watched 2012. The conceit that the world will end last year must be getting tired by now, but I’d been curious about the movie since it came out three years back. As I suspected, there was plenty of religious banter as the putative version of us prepared for the end of the world. I noted that the little boy of the average family that managed to make it all the way to China to seek rescue bore the name of Noah. When the animals were being airlifted to the rescue station with its titanic boats meant to float out the world wide flood, it was clear that the myth of the ark was alive and well. (As I hope all of you reading this in the future are.) So this disaster movie turned out to be a bit of harmless fun, but I nevertheless shuddered at the implications. Those chosen to survive were, naturally, those who could afford to find a place onboard the secretly constructed arks. As even some of the film’s characters recognized, those who had money could buy a place on the ark, and of course they did. I do wonder what their brave new world would have been like. The whole idea of wealth has to do with the perceived value of specific commodities, and apart from our last minute stowaways, you can bet that everyone on board wanted their assets valued highest. Once the waters receded, if I recall the story at all, sacrifices would be made. Even the opening of the decks and the buzzing of helicopters like doves and ravens did Genesis proud.

I just watched 2012. The conceit that the world will end last year must be getting tired by now, but I’d been curious about the movie since it came out three years back. As I suspected, there was plenty of religious banter as the putative version of us prepared for the end of the world. I noted that the little boy of the average family that managed to make it all the way to China to seek rescue bore the name of Noah. When the animals were being airlifted to the rescue station with its titanic boats meant to float out the world wide flood, it was clear that the myth of the ark was alive and well. (As I hope all of you reading this in the future are.) So this disaster movie turned out to be a bit of harmless fun, but I nevertheless shuddered at the implications. Those chosen to survive were, naturally, those who could afford to find a place onboard the secretly constructed arks. As even some of the film’s characters recognized, those who had money could buy a place on the ark, and of course they did. I do wonder what their brave new world would have been like. The whole idea of wealth has to do with the perceived value of specific commodities, and apart from our last minute stowaways, you can bet that everyone on board wanted their assets valued highest. Once the waters receded, if I recall the story at all, sacrifices would be made. Even the opening of the decks and the buzzing of helicopters like doves and ravens did Genesis proud.

The end of the world is a funny concept. Those of us who experience the world as mortals can’t really image the place without us, so I suppose it is natural enough. Nevertheless, the tone of the last four apocalypses I remember has been distinctly religious. There was a serious scare (perhaps local, because no internet existed) when I was in tenth grade. The next one I recall was Y2K, a silly episode where even priests I knew were seriously worried. With the Camping and Mayan “predictions” coming so close together, some no doubt supposed the Big Guy had it in for us all. When Christians tell the story it’s always the version with God glaring at us, belt in hand. Remember what Homer Simpson says of the song he wrote: “I’ve come to hate my own creation. Now I know how God feels.” Our cultural sense of disapprobation could be better addressed by helping those in need rather than building arks (or tax write-offs) for those who require no more to live like petty emperors. Emphasis on petty.

The world didn’t end and I wasn’t really worried that it would. The fact is we don’t need God to design an apocalypse for us because we’re very good about engineering our own. Unequal distribution of goods and services throughout a world where means exist for alleviating the suffering of countless numbers of the poor and disadvantaged has already created a purgatory on earth. We don’t need a Mayan calendar, or a New Testament whose message of compassion is overlooked in favor of its putative apocalypse, to show us the end of time. But since we made it to 2013, perhaps we should consider this a stay of execution. Let’s use our post-apocalyptic future wisely and hope humanity will live up to its name. And maybe it’s time for a new calendar.