A friend, during a time of trouble, quoted from Charlie Mackesy’s The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse. I immediately ordered a copy. The word “magic” gets thrown around a lot, but this book holds real magic. It is perhaps the wisest book I’ve ever read. Do yourself a favor—if you haven’t read it, find it in a library, or order it from Bookshop.org or Amazon. Visit a local bookstore, and if they don’t have it, ask them to order it. If people read books like this we’d never need to worry about things. And if everyone read it and took it to heart, we’d never need to worry about anything again. There’s much to be said about believing in yourself and believing in the power of love. At the end of the day they speak for themselves.

The book is for any age reader. Handwritten and illustrated, it’s written at the level of a children’s book that takes less than an hour to read. Its message feels almost radical, however. That having been said, the young adult generation, I’m given to believe, grew up with the kind of outlook Mackesy offers. The book struck me particularly relevant and necessary, something for those of us in the over forty crowd. I understand the tendency to grow more conservative as we age and I believe it’s because we’re afraid. Ironically, the book addresses the issue of fear, pondering how life might improve if we could get beyond being afraid of things.

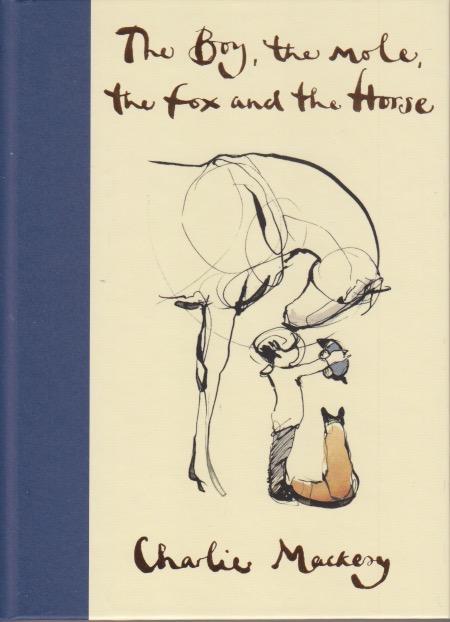

The artwork is beautiful and the words are inspired. This is an eminently quotable book. Mackesy has been an artist by trade. We can learn so much from such humble artists, if we’re willing to listen to them. Kindness, love, and simplicity are gifts we often wish not to accept. It’s very easy to hate and selfishness comes naturally to people. And when we get together we tend to complicate things. Once in a while we should set aside the complexities of life and make time for a simple story that reminds us of what’s really important. Of course, those of us who read are prone to thinking of ways the world could be a better place. Being open to love instead of hate, trust instead of fear, and hope instead of dread doesn’t come naturally. That’s why it’s so helpful to have books to remind us of this. Especially when such a book won’t even require an hour of your time. I’ll be coming back to it time and again.