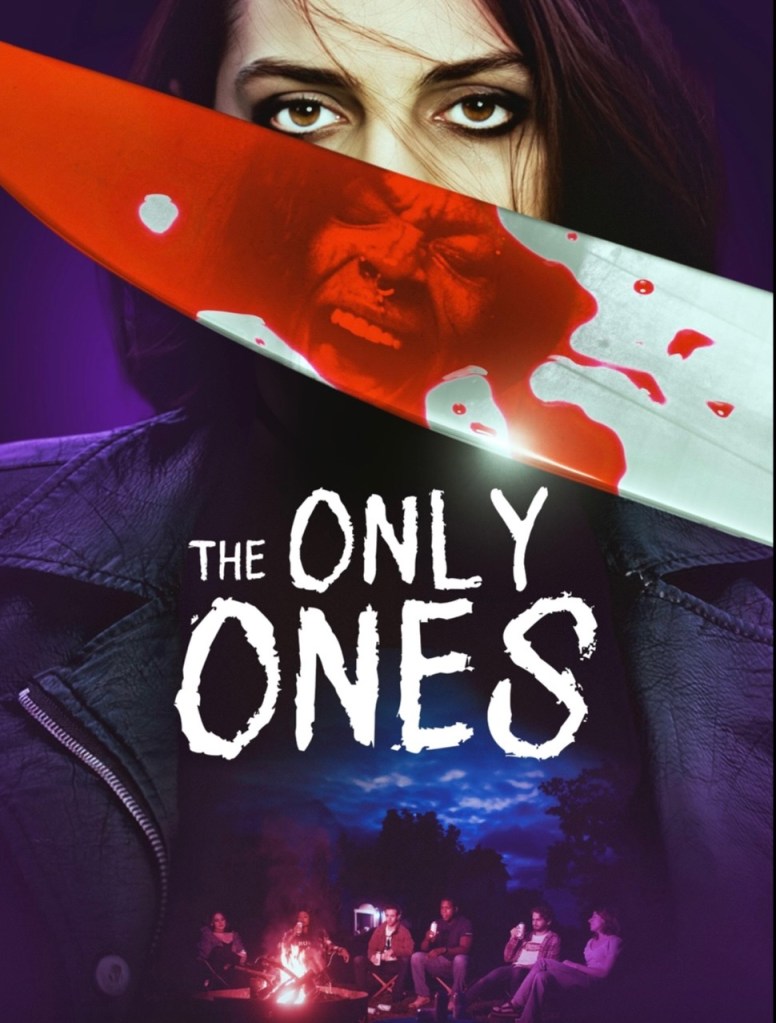

Slashers aren’t my favorite horror films. As I’ve suggested in some of my unpublished writing, horror should be dismantled as a “genre” since so many different types of movie are collected together under its rubric. That having been said, The Only Ones is an amazing low-budget, independent slasher. For one thing, it references so many other horror movies that it is mind boggling. Just a few influences: Deliverance, Scream, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Blair Witch Project, and just about every movie that has a bunch of young people going to a remote location by themselves. It’s complex and thoughtful. A love story and a reflection on religion and horror (only in a minor way, but still). And piecing together what led to the eight deaths would require an article all by itself. And it’s a film with heart as well as gore. A spoiler follows.

The basic idea is that the six young people are primed for a horror movie outcome by one of their number who’s a true crime podcaster. They’re going to the remote house of the uncle of one of them since the uncle passed away and they are helping settle the estate. A couple of campers have innocently trespassed in the house and a violent confrontation with them sets the tone for all of what follows. The movie is also a reflection on how a weapon in the midst of any group leads to violence. One of the kids has a gun and the threat of that weapon leads to people killing one another without ever really stopping to figure out what happened. A final girl survives the two nights, and when the police ask her what happened, so honestly says she has no idea.

The movie has some flaws, and early on I was eager to note them all, but the story sucks you in. The deaths, in the end, are all pointless. They begin because of a misunderstanding with a violent threat being used instead of trying to understand what happened. This brings the movie up to the level of actually having a message. Many slashers seem to settle on “traditional values”—don’t use drugs, have premarital sex, or in any way offend the world envisioned in the 1950s. Those who are killed have violated some principle that keeps society the same forever. The Only Ones has something deeper to say. The characters are self-described outcasts. The one who survives is the one who learned to love. And bringing weapons into any situation leads to a Chekhovian resolution.