In a disappointing email, Amazon Prime has announced that its free movie streaming of select titles for members will now be subject to commercials. I suppose that’s little difference, actually, from the way I watched most movies growing up. I watched them on television before cable, and commercials were a necessary evil then. Speaking of evil, I decided to watch a film that I missed in my childhood. It was better than expected. The Creeping Flesh suggested itself by star power. Although not a Hammer film, it features both Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee as a pair of mad scientists. Interestingly enough, it struggles with the question of evil and, appropriately enough, has an ambiguous ending. There’ll be spoilers below, but since the movie was released over a half-century ago, I’ll use them with a clear conscience.

Cushing’s character, Dr. Emmanuel Hildern, has discovered a skeleton of pure evil personified. It will become the end of the world once it’s revivified. Meanwhile his half-brother, Dr. James Hildern (Lee), runs an insane asylum where questionable treatments are performed. The brothers are rivals and although not quite estranged, they don’t work together. It’s actually late in the movie that the corpse of evil is resurrected, but in the meanwhile Emmanuel’s daughter goes insane, like her mother had, after being given a vaccine against evil that her father devised. Her Ms. Hyde-like exploits make her dangerous to Victorian society and she has to be committed to her uncle’s asylum. The being of evil attacks Emmanuel and we find him at last in his brother’s asylum. James is explaining to his assistant that this madman thinks he is his brother and that another patient is his daughter. The film has been a fantasy in an unbalanced mind. Except for a suggestion in the final close-up that the story of the corpse may indeed have actually happened.

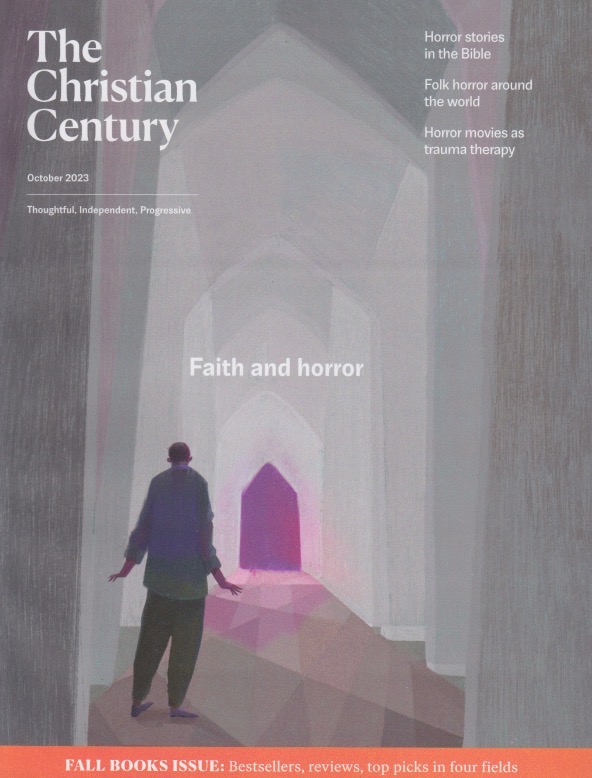

What particularly intrigues me is the discussion of evil in the film. Emmanuel claims that it is like a virus, an actual physical pathogen. He believes it can be prevented by a vaccine. I’ve actually read some academic work in the past few years that suggests that “sin” is an actual, almost physical thing. A kind of cosmic force. More sophisticated, of course, but not entirely unlike what this horror film was suggesting fifty years ago. The Creeping Flesh isn’t a great movie—it suffers from pacing and a somewhat convoluted plot, but still it demonstrates why I keep at this. Horror often addresses the same questions religion scholars do. And occasionally it even seems to anticipate more academic ideas, fed to a viewership making the same queries. It’s worth watching, even with commercials.