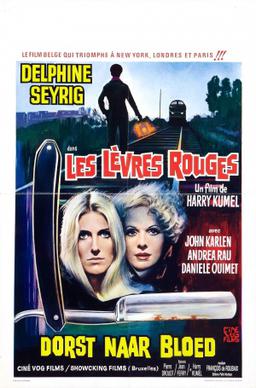

Vampire movies have always been a guilty pleasure. The thing is, there are so many of them that watching them all would be the task of a lifetime (and a substantial budget). Those of us who are constantly looking for, shall we say, new blood, can find that our lack of knowledge extends back for years, particularly if a movie didn’t make it big in our home country. Daughters of Darkness is an early Euro-horror about Elizabeth Báthory. A stylish, almost art house movie, what particularly struck me about it is that it was very well written. The use of blood is restrained, given the topic, but verbal descriptions of Báthory’s excesses makes for a particularly gruesome scene. So, about the story. (This is from 1971, so I won’t worry about spoilers too much.)

A young couple (his backstory is inadequately explained in the movie, apart from being aristocratic), newlyweds, are headed to introduce her to his family. Stefan (he) isn’t exactly the ideal husband (played convincingly by John Karlen), but Valerie (she) really wants to meet “mother.” Stefan stalls the trip, and, in the off season, the couple have a luxury hotel to themselves. Then Elizabeth Báthory shows up with her “secretary.” Stefan is a little too interested in violence, as a string of murders make the headlines. Meanwhile, Elizabeth begins making moves on Valerie. We come to understand fairly early on that she’s a vampire, but no fangs appear and she’s always impeccably dressed and sophisticated. Her secretary, who is having second thoughts, is accidentally killed while setting up Stefan as an unfaithful husband—again, the writing here is quite good—and Valerie becomes Elizabeth’s new secretary.

There’s a strong feminist aspect to this film, perhaps because Delphine Seyrig (Báthory) was a prominent feminist and would be attracted to such roles, it would seem. The daughter of an archaeologist in Beirut, she supported women’s rights and there appear to be elements of this in the movie, although it was written by four men. I was a bit too young for this movie when it came out, and art movies wouldn’t have stood a chance where I grew up, at least not in circles my family knew, so although Dark Shadows mainstay Karlen took a rare male lead role in the movie I’d been completely unaware of it. But then, vampires are that way, aren’t they? They tend to be old and well-hidden in the shadows. Then they come at you with a bite when you least expect it.