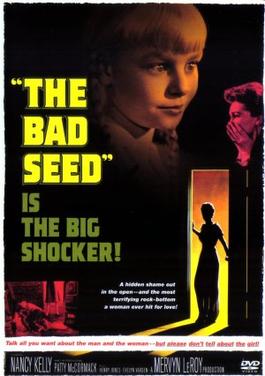

The Bad Seed is one of the scariest movies Stephen King lists from about 1950 to 1980. Like many movies from before my time, I was unaware of it. Projecting it back to 1956, when it was released, it’s pretty clear why it had trouble making it through the Production Code Administration. Showing no blood or gore, this two-hour feature may seem to drag a little but it ends up in a very dark place. I’ve never read the novel upon which it was based, but I’ve learned that the ending had to be changed because evil doers, according to the PCA, cannot go unpunished. In fact, the ending is so dark that the director, Mervyn LeRoy, had the cast do a walk-on introduction when the movie was over, assuring the audience that this was just fiction after all.

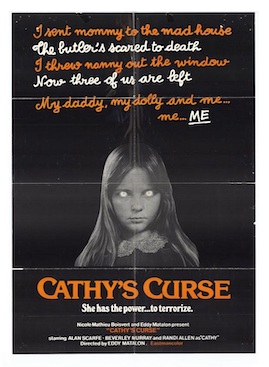

The shock comes from a child psychopath. So much so that Rhoda Penmark has become a character in her own right. A sweet, innocent eight-year-old girl, she lies nearly as well as Trump and has skeletons in her closet. Skeletons an adult shouldn’t have, let alone an eight-year-old. Not only is she a sociopath, she’s convinced all the adults that she’s just as innocent as she acts. The movie moves into psychological territory quite a lot, including a discussion of “nature or nurture” as the source of human evil. The title of the film gives away the conclusion on that front. Some children are born bad. What’s more, this is the result of genetics, according to the story. Rhoda is the child of an adopted woman—her adoption has been kept secret from her. Eventually her father confesses that she was the child of a notorious serial killer, abandoned and adopted by loving parents. Rhoda herself is raised in a loving, stable home, but she is her grandmother’s daughter.

I won’t spoil the ending, but I will say that if they had ended it at the hospital scene it would’ve been scarier. The book, apparently, ends the scarier way. I do have to wonder if Alfred Hitchcock was familiar with the tale in some form. The movie was released four years before Psycho, but then again, that was based on Robert Bloch’s book. Maybe he’d read the original. In any case, I’d been watching King’s list of scary movies and mostly finding myself unbothered. A couple of his choices: Night of the Hunter, and now The Bad Seed, have managed to rattle me a bit. Even with its nearly seventy-year-old sensibilities, the latter still scares.