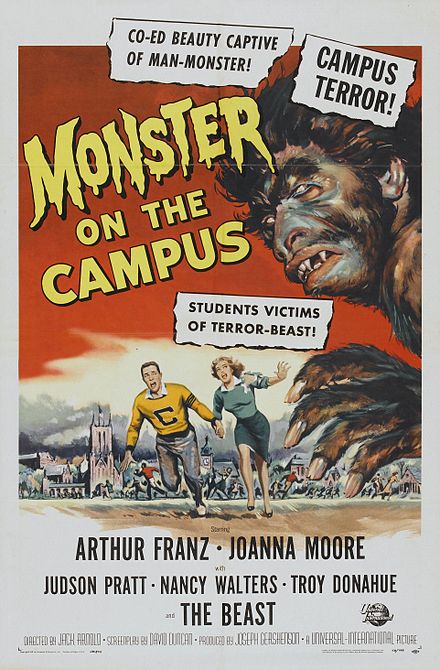

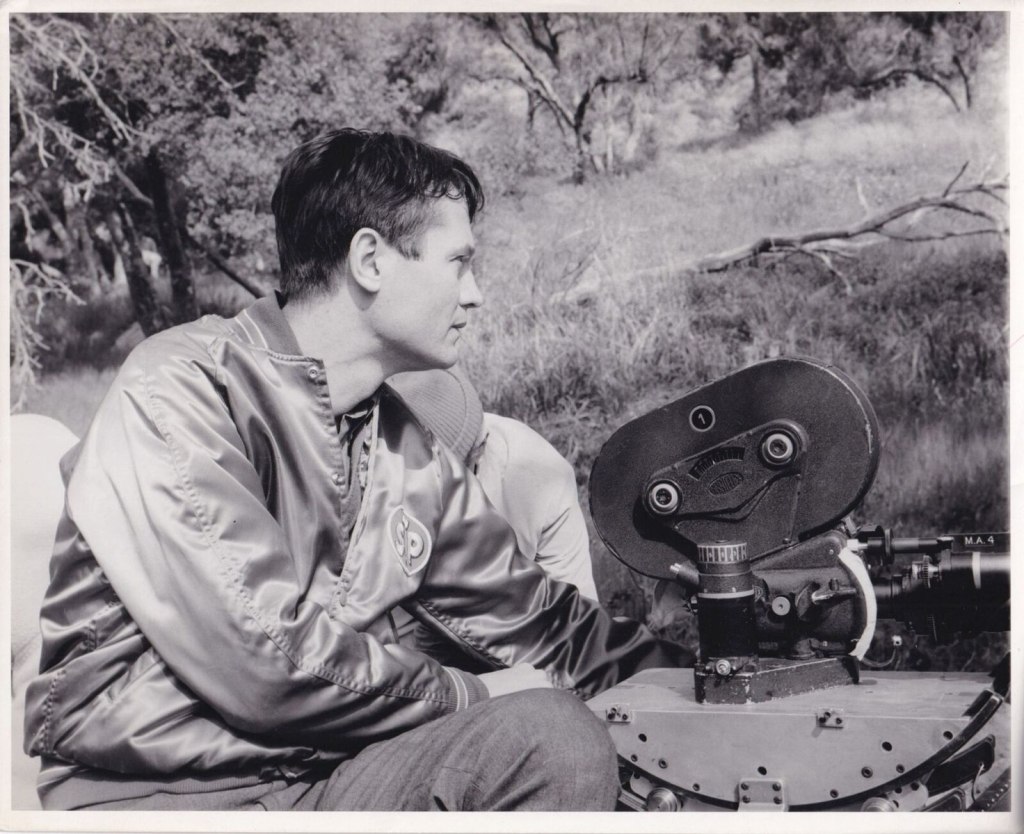

Universal was the studio that gave America its monsters. Well, it wasn’t Universal alone, but the initial—almost canonical—line-up of monsters were Universal productions. As horror grew to be more influenced by science-fiction in the 1950s, Universal kept at the monster-themed movies, cranking out many that I missed and on which I’ve been trying to catch up. Monster on the Campus is interesting in a number of ways. Directed by Jack Arnold, of Gilligan’s Island fame (or future fame, since this movie was earlier), it’s a story built around evolution. Pipe-smoking professor Donald Blake has a coelacanth delivered to his lab. Unbeknownst to him, the prehistoric fish had been irradiated with gamma rays to preserve it—as well as being shipped on ice. The dead fish is about to create problems.

A dog laps up some of the blood (it started to thaw) and becomes a vicious evolutionary throwback. Then Professor Blake cuts himself on a fish tooth and sticks his hand in the contaminated water. He becomes a murderous caveman, but the effect is only temporary. A dragonfly eating the fish transforms into a prehistoric insect that the professor kills, but its blood drips, unnoticed, into his pipe. He changes and murders again. Finally it dawn upon him that he was responsible for the murders. In a remote cabin he sets up cameras and injects himself with the radioactive coelacanth plasma and ends up killing a park ranger. Finally, he injects himself so that following police officers will shoot him to death. Rather a bleak story.

The film has been read as social commentary since its “rediscovery,” but what caught my attention was the easy acceptance of evolution. This was the late fifties and the creationist backlash was still pretty strong at the time. If evolution didn’t occur, the professor (and dog and dragonfly) couldn’t have become their atavistic selves, giving the movie its plot. The classic Universal monster of the decade was the Gill Man—aka Creature of the Black Lagoon—also an atavistic throwback to an earlier time, but also a divergent branch of evolution. Creature was also directed by Jack Arnold, but four years earlier. It began with a quote from Genesis 1, bringing creation and evolution together. The title Monster on the Campus offers many possibilities for co-ed mayhem, but instead opts for a scientist who gets caught up in the tangle of evolution. The movie was near the end of Universal’s monster run, but in the sixties horror would change forever. This was a little fun before things got serious—horror school was about to start.