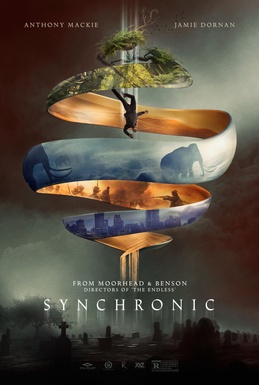

The philosophically adept movies by Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead can be addicting. At least for a certain kind of viewer. These are independent films and they’re smart and worth the effort of tracking down. Often they fall into both sci-fi and horror, but generally horror of the existential variety. And they have social commentary. Synchronic is gritty, delving into drug culture (as some of their other movies do as well) and taking its title from a fictional drug. Synchronic, the drug, distorts the taker’s sensation of time. If the user is young—their pineal gland hasn’t calcified—the drug physically transports them to the past. Adults only experience it as ghostly images rather than physical displacement. Two EMTs, Steve and Dennis, keep finding victims of the drug. Steve is a black man with brain cancer that keeps his pineal gland from calcifying. Dennis, a family man, loses a daughter to synchronic—she gets lost in time. Steve decides to save her.

Here’s where the social commentary really kicks in (although it’s been there from the beginning). A black man traveling back in time in Louisiana is at a distinct disadvantage. Dennis is white but his brain won’t allow him to travel back physically. Not only that, but it was Steve who took the initiative to find out how the drug works. You spend only seven minutes in the past, unless you miss being in the right place when the drug wears off. If you miss the return, you’re stuck forever in the past. That’s where Dennis’ daughter is. She’s caught in New Orleans in 1812. Louisiana was, of course, a slave state. Steve faces enslavement if he doesn’t make it back in time. I won’t say how it ends, but it leaves you thoughtful.

Many “white” Americans feel that Black Lives Matter is too “woke” for them. They seem to think everything is now free and equal. It isn’t, of course, and those who are willing to look see that African Americans have an extra layer of struggles that they constantly face. The movie addresses this as well. When assisting an overdose victim after he misplaced his uniform, Steve is mistaken for a criminal by the police at the crime scene. This despite the fact that the white officer who initially detains him, knows him. A black man out of uniform must be up to no good. I can’t believe that I went so many years without knowing about Moorhead and Benson movies. Be careful if you start watching them—they can be addicting.