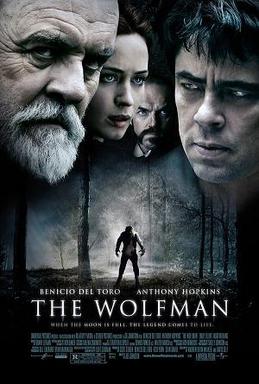

Time has a funny way of distorting perceptions. I remember when The Wolfman (2010; please, I’m not old enough to have seen the classic initial release in 1941) came out. I’d already started this blog by then, and I was occasionally watching and writing about horror movies. Initial reports said this reboot was too violent and bloody. I had the impression that it’d done well at the box office, but I didn’t see it. I found a used copy on DVD several years later and still I waited to watch it, a bit afraid from the initial assessments I’d read. (I tend not to read reviews or watch trailers before seeing a movie—I prefer to come in fresh.) All of this is to say I finally got around to seeing The Wolfman and I was disappointed. I really wanted to like it too. The wolf man was my favorite classic monster as a kid.

I do need to praise the gothic setting and landscape cinematography. This is beautiful and well done. Part of the problem is the way the story is changed. Another is that, apart from The Silence of the Lambs, Anthony Hopkins doesn’t seem to fit the horror genre very well. Claude Rains made a believable Sir John Talbot, despite being so much smaller than Lon Chaney. Hopkins has trouble pulling it off. It could be poor directing, I suppose, but it was difficult to take him seriously. And two werewolves? That suggests just a little too much CGI. Still, there are some good moments. I did appreciate Sir John encouraging his son to let the wolf run free. I suppose if you’ve got a werewolf issue, having a dad to talk you through it would be a good thing.

Werewolves, like most classic monsters, are thinly disguised psychological tendencies. Civilization isn’t always easy, even for social animals like our own species. There’s a werewolf inside. Transformation, however, always suggested redemption to me. The ability to become something better. I saw The Wolf Man as a parable. That may have been unusual for a kid, but when religion and monsters come together strange things can happen. The wolf may be angry, but it need not be dangerous. It turns out that I really didn’t have to wait thirteen years to see this movie. I’ll probably watch it again for the points it scores on the gothic scale. The action features aren’t necessary for a good monster flick, though. The 1941 version worked just fine.