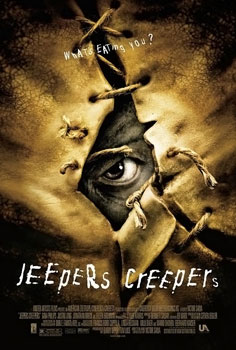

There’s some symbolism here that I haven’t had time to sort out. (Some of us need time to just sit and think—time that work won’t allow.) I’d been wanting to watch Jeepers Creepers for quite some time but streaming services said it was unavailable. I suspect that was because a sequel has been running in theaters and those who own the rights want to capitalize on it. So it goes. When it finally did show up on Freevee, so you have to subject yourself to commercials, I had to see it. Now I need some time to think. In case you’re even slower than me, the film involves a couple siblings driving home for spring break when they encounter a monster/demon, Creeper.

Creeper smells peoples’ fear and consumes parts of those who have something it needs to regenerate itself. The brother and sister encounter Creeper on one of those long stretches of road without civilization that you find in parts of America (in this case, the unspecified south). I won’t spoil the ending, but for my money (or actually, Freevee patience), the first half is pretty scary. The whole is not bad either. So what do I need to think about? Well, Creeper stores its victims’ corpses in a church basement. The church is abandoned, but still. This overlap between religion and horror is an aspect that has fascinated me time and again. Shouldn’t a church be a safe place? (For many of us, that’s a myth long debunked.) Is it because it’s abandoned that a demonic monster has moved in? Or does religious symbolism not bother it? Or perhaps attract it?

Not only that, but the movie also has a prophet. While she’s not called that, this local woman has dreams of things involving Creeper that haven’t happened yet. Like Cassandra, however, everyone ignores her. It seems that Jeepers Creepers experienced a budget cut during production that led to a rewritten, and cheaper, ending. While I won’t spoil it, I will say that it is a bit of a letdown from how the film started. A lot is left unexplained, but the story is pretty good and the acting, at least by the siblings, and the always entertaining Eileen Brennan, was impressive. They have a way of conveying fear that’s believable and contagious. The religion theme, however, appears to have been dropped once the church burns down. It may be that it was somehow revisited in the ending that money forced to change. Regardless, it is worth watching, and, if you have the time, pondering.