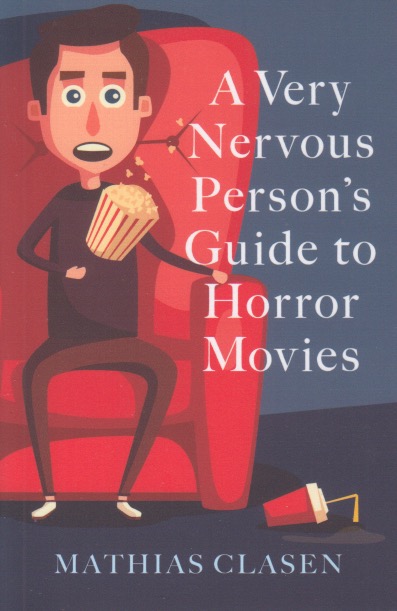

I’ve lost track of how many times it’s happened, but it has been relatively few. Someone I don’t know will approach me and ask me to post about something on my blog. Sometimes they’ll even send me a book to highlight. Perhaps not the most effective way to build a library, I’ll admit. And some of the books haven’t been great. I admire them nonetheless. It takes great effort to write a book. And not a small amount of faith, too. Many books—perhaps most—never get published. A great many are self-published. (Those who work in publishing can be a stuck-up lot sometimes.) Even those professionally published can use a push from time to time. On this blog I’ve actively resisted the urge to make it about one thing. Why? Is life just one thing?

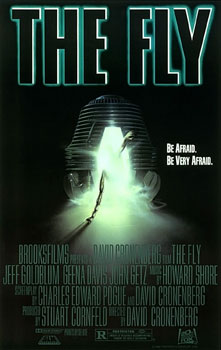

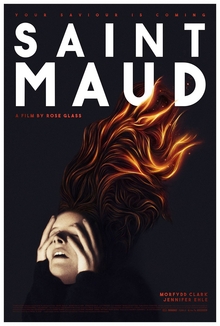

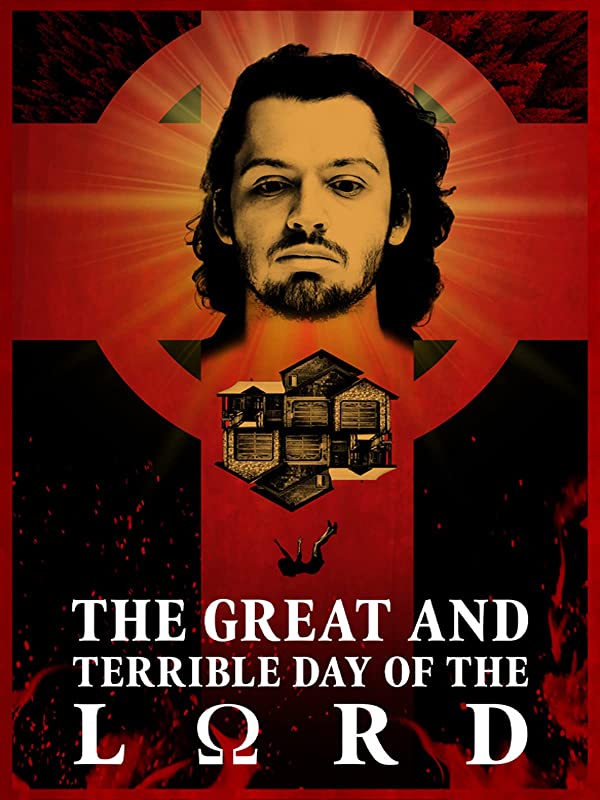

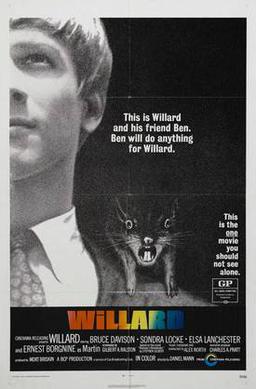

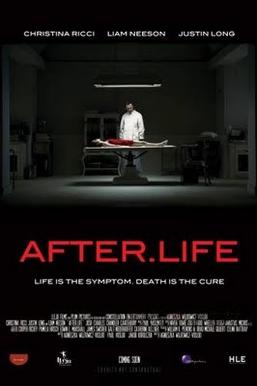

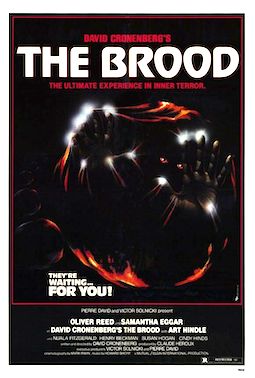

In a recent conversation I laid out for someone new what had been my research agenda as a young professor. It had a direction still reflected in some of the categories you’ll find on the right column of this blog. After writing on Asherah, I was going to give similar treatment to the other ancient goddesses attested at Ugarit. This was perhaps ambitious for an academic waif at Nashotah House, but it was well underway. My book on Shapshu was making good progress when the market (that dragon to every St. George) led friends to suggest turning biblical, which led to Weathering the Psalms. A new research agenda—explore the weather terminology (the meteorotheology) of other biblical books—arose. There were storms, after all, becalmed over lakes. Horror entered in the jobless period and beyond.

And social justice. I’m not a thrice-failed minister for nothing! In fact, a recent freebie was a book on social justice. I have a colleague as interested in monsters as me. This particular scholar had decided to focus on the cause of the poor. Even economists are starting to say the unequal distribution of wealth is hurting us. While the rich fly to space on personally owned rockets, the rest of us have trouble filling up at the service station, even if we have jobs. So it is that this blog is eclectic. A friend told me early on that it would be more popular if I just stuck to one topic. That’s probably true, but my mind can’t settle down like that. And when people send me things to talk about, I’m happy to do so, if it fits somewhere in my mind.