Now that I’m safely ensconced back in the daily work routine, I spend some time thinking of the scary movies I had time to watch during my “free time.” Well, I actually thought about them then, too, but I had so many other thoughts to write about that I kept putting it off. That, and the fact that some of the movies were about demonic possession and the juxtaposition of holidays and demons just didn’t seem to fit, kept me from expounding. Why watch such movies at all? It’s a fair question. I tend to think of it as part of a larger thought experiment—wondering what such movies might tell us about being human.

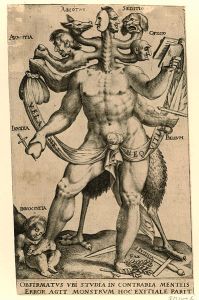

A few weeks back I wrote about The Exorcism of Emily Rose, based on the true tragic story of a young woman who died after a prolonged exorcism. After that I watched The Last Exorcism, The Rite, and The Possession. (I’m such a cheerful guy, as you can see, and this may be why I inhabit an isolated cubicle at work.) This array of movies, held together by the common chord of the reality of demonic possession, also brought together the standard sociological division of Protestant, Catholic, and Jew. The Last Exorcism is a Protestant-based treatment of what is generally considered to be a Catholic subject. That connection is affirmed in The Rite. The Possession, however, gives us a Jewish demon and a rare representation of a Jewish exorcism (acted by Matisyahu, no less!). What emerges from watching all of these films together is that demons are an inter-denominational problem, even in a scientific world. Carl Sagan wrote about the demon-haunted world, and it continues to exist, it seems.

But these are movies we’re talking about. Not reality. Nevertheless, The Rite and The Possession are also said to be based on true stories. We do live in a mysterious world. Evolution has developed reasoning as a practical way of dealing with life in a complex ecosystem. It is a survival mechanism. So is emotion. We sometimes forget that both thought and feeling are necessary for survival in our corner of the universe. Neither one is an end in itself. We can’t quite figure out how these two features of the human brain work together. There are, in other words, some dark corners left in our psyches. I suspect that’s why I find such movies so interesting. They’re not my favorites, but they do serve to remind us of just how little we know. And that’s a scary thought, given how we’ve learned to possess this planet.