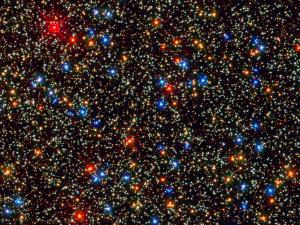

I sometimes wonder if science would have the appeal that it does, if it didn’t have religion to shock and awe. I’m thinking of not only the fact that The Humanist magazine quite often has a focus on religion, but even websites, irreverently named to make the sensitive blush, frequently use it as a foil. My wife likes the site now more commonly known as “IFL Science!” Web acronyms have taught us what the second of those letters denotes, but perhaps because making the name more family friendly leads to more hits, it’s been muted a bit. In any case, the most recent post I’ve seen has to do with that marvelous Hubble image of interstellar gas and dust columns where stars are being born, know as “The Pillars of Creation.” Apart from the stunningly beautiful images, I’ve always been taken by the way that implicitly or even subliminally, concepts of deity lie behind this scene. When the image was first published, I remember staring at it in rapt fascination—here we had stolen a glimpse into the private chambers of the universe. We were seeing what, were we in the midst of, would surely prove fatal. It is like seeing, well, creation.

Creation is enfolded in the language of myth. Reading the description of this great, gaseous cloud, we are told of the tremendous winds in space (what I had been taught was an utter vacuum) where dust is so hot (I was taught space was frigid) that it ignites into stars, like a silo fire gone wild. It’s like witnessing the moment of conception, although Caroline Reid tells us the dust will be blown away in 3 million years. Perhaps ironically, scientists are scrambling to study it before that happens. Or before that will have happened. At 7000 light-years away, it will have been gone as long ago as Sumerians first put stylus to clay before we know of it. We still have a couple million years for a good gander. And the Sumerians, the first writers of which we know, were writing stories of creation.

It is really a shame that science has, in general, such an antipathy towards myth. As scholars of biblical languages, indeed, nearly any language, know, the language of myth and poetry is especially useful when standard prose breaks down. “Wow!” is not a scientific word. Nor is “eureka!” What other response, however, can there be to seeing the act of creation with our own eyes? Meanwhile there will be those who use science to belittle the worldview of the myth maker and and thinker of religion. Our world, it is widely known, is that of superstition and ignorance. We are those who think only in shallow pools and deny the very reality that is before our eyes. That reality can be full of stunning beauty, but were we to describe it in terms empirical, we might have to keep the interjections and useless adjectives to a minimum.