After watching Hugo, and wishing that the story were history, I found a copy of Brian Selznick’s The Invention of Hugo Cabret. Martin Scorsese’s adaptation is fairly close to the book but there are, of course, additions and omissions. One key character is left out and some subtleties to the book didn’t find their way obviously into the movie, or at least not until having read the book. The story of Georges Méliès’ life in the book is largely accurate. Hugo, however, and Isabelle, are fictional. As is the automaton around which the story is based. The lovable train station vendors in the movie are quite a bit less lovable in the book. And the station inspector isn’t shown until late in the story and he doesn’t have the leg brace that lends a kind of steampunishish vibe to the film.

Apart from being a tale of redemption—in real life Méliès’ rediscovery didn’t lead to an end of his poverty—the story is an exploration in psychology. Méliès lost his dream job due to competition after the First World War. The book makes clear that the clicking of heels drives him to rage because his films were reputedly melted down to make shoe heels. The story in the book goes so far as to say that ghosts follow those who clack their heels loudly. The ghosts, of course, are those of Méliès’ lost success as a filmmaker. One of the reasons this story appeals to me is that I too lost a job that gave my life a sense of purpose. My writing largely does that now, even if it doesn’t sell. I can relate to a man who is ready to retire but can’t, daily reminded that he once had a satisfying job but now has to sit behind a desk all day.

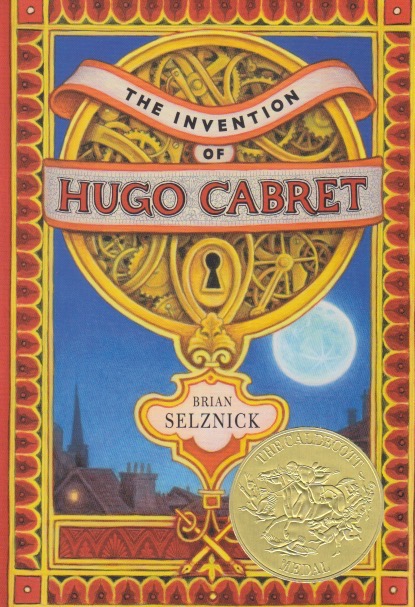

The Invention of Hugo Cabret is a book for younger readers. About half of the book’s 500-plus pages are illustrations. The images include stills from Méliès’ surviving films, but mostly drawings by Selznick. The focus on the young people makes this a children’s book, but the truths it tells of adults with lost dreams are especially appropriate for those who’ve learned that life isn’t always kind to dreamers. The book, like the movie, inspires me to seek out the surviving films of Georges Méliès and think of what can indeed happen to those who dare to dream, even when the world has already discarded them as irrelevant.