I need more time to prepare for Imbolc. Or Groundhog Day, whichever you prefer. Candlemas for you Catholic holdouts. February 2 has the trappings of a major holiday, but it lacks the commercial potential. Too many people are still working their way out from under Christmas overspending and tax season is just around the corner. Still, I think it should be a national holiday. My reasoning goes like this: since the pandemic our bosses now have our constant attention. They’re in our bedrooms, our living rooms, our kitchens. I see those midnight email time stamps! We’re giving them a lot more time than we used to and seriously, can they not think about giving us a few more days off? Some companies strictly limit holidays to ten.

Others, more progressive, have simply dropped the limits on paid time off. And guess what? The work still gets done. I could use a day to curl up with a groundhog, or to go milk my ewes. (Being a vegan, perhaps I could just pet them instead.) What’s wrong with maybe two holidays a month? (We don’t even average out to one per month, currently.) I always look at that long stretch from March, April, and nearly all of May with some trepidation. That’s an awful lot of “on” time. (Our UK colleagues, of course, get Easter-related days and a variety of bank holidays. Their bosses, I understand, would rather go with the more heartless American model, but tradition is tradition, you know.) What if I see my shadow and get scared? What am I to do then?

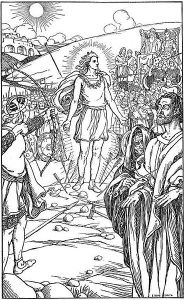

Imbolc is part of an old system for dividing the year into quarters that fall roughly half-way between equinoxes and solstices. I go into this a bit in my book, The Wicker Man, due out in September. That movie, of course, focuses on Beltane, or May Day, but the point is the same. Look at what happens when you deny your people their holidays! You’d think that the message that showing employees that you value them makes them more loyal might actually get through. Businesses, however, have trouble thinking outside the box. Take as much as you can and then ask for more. What have they got to lose by giving out a few more holidays? Otherwise each day becomes a repetition of a dulling sense of sameness. Rather like another movie that focuses on this most peculiar holiday.