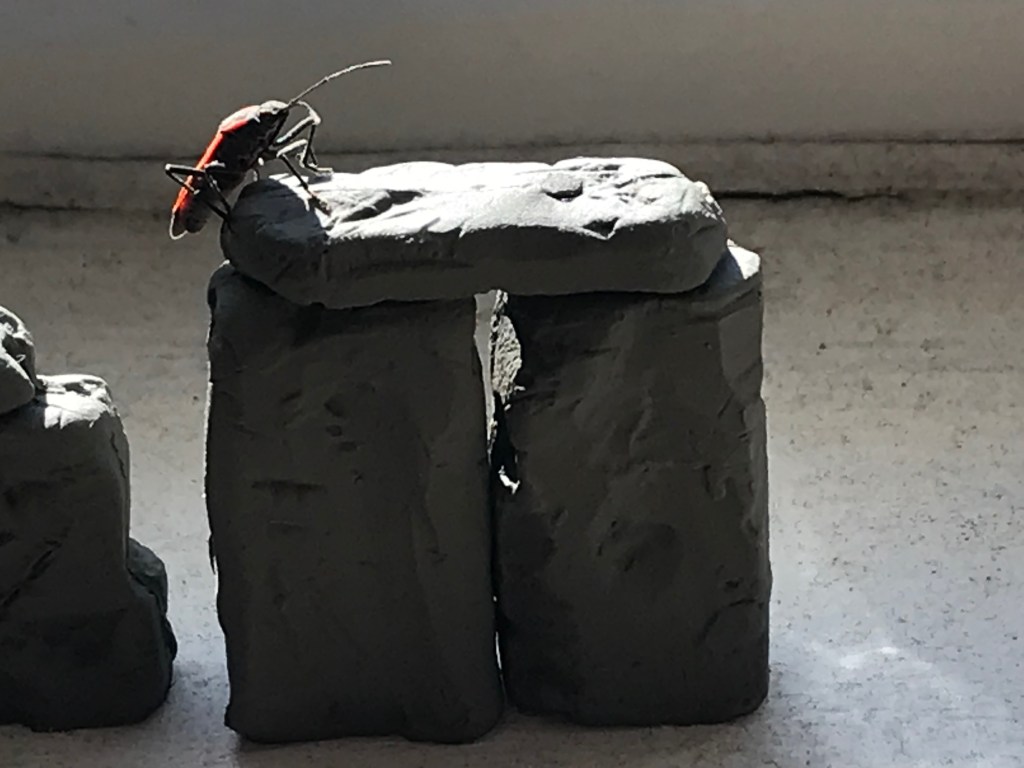

There’s a scene in Disney’s Hercules where Thebes has just been through a bunch of unnatural disasters sent by Hades to lure Hercules into the open. The people, visibly shaken by the tragedies are talking about their need for a hero. Then a locust hops in. An old man says that does it, he’s moving to another city. So with yesterday’s super soaker around here—we’ve had our roof completely replaced—water was still getting in. I’m no expert, but it looks like it was condensation rather than roof leaks proper. The air was saturated and cold, while inside it was at least a few degrees warmer. I got up to find buckets scattered around that my wife had set up after I’d fallen asleep. Then a boxelder bug appeared on the curtain in my study. The insect on top of other misfortune. It’s classic.

That’s because insects swarm. We live in an older house (the only kind designed with space that can be used for books). It doesn’t have wooden siding, but boxelder bugs like to overwinter in the walls. I really can’t figure out why because in nature they winter in, well, boxelder trees. Or a maple. There are no boxelder or maple trees near our house, but they seem to like it nevertheless. The problem is they get inside, in numbers. We try to run a catch and release business. It seems decidedly unfair to kill a harmless bug for doing what human-altered climate tells it to do. When the heating kicks on, their insectoid brains tell them it’s spring and they crawl out looking for food. Well, we don’t have any trees they like growing inside, so they wander about aimlessly. I catch them and take them outside, figuring maybe they can find, I don’t know, a tree?

Usually when winter’s serious chill sets in, they go dormant. This year we’ve been hovering between freezing and not, and when the sun comes out—which it sometimes does—they awaken. They must be confused. Somehow they don’t realize that the world has changed around them. Going about their daily bug business (nothing seems to eat them—apparently they taste bad) the climate has broken their hibernation into segments of a few days at a time. Perhaps they’re cranky when they crawl up the curtains, or across my desk (they pretty much stay in my study). At least they don’t sting. They’re not bad enough to make us leave Thebes, but it would be wonderful if they’d wise up to global warming, and maybe plan in advance. Or maybe they’re waiting for a hero.