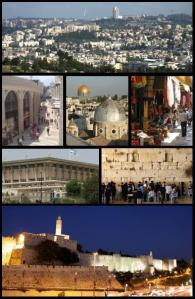

At first glance it may not appear to be much. A small chunk of rock, probably limestone. Hardly large enough to be used in a sling against a giant in a pinch. Still, it is special. What makes this rock special is the context from which it was removed. A friend has recently returned from Israel and he brought this rock for me. It is from the Mount of the Temptation, atop which sits a lonely monastery cared for by a single, elderly monk. The thought of someone thinking of me in such a (literally) God-forsaken wilderness is touching. My brief travels through the desert of Judea offered plenty to occupy my restless mind. I’m pretty sure we zoomed by the base of the Mount of Temptation in an air conditioned bus one day on our way to somewhere less desolate. Or more. The sharp-voiced little skeptic in my head immediately kicks in: if Jesus was alone when tempted, how could anybody possibly know where it happened? I can’t picture him leading a tour there later—“and this is where I almost turned stone to bread; don’t those pebbles look like challah to you?”

But then, it’s not about historical accuracy. This little stone in front of me is a symbol. Broken off of the karst geography of the rocky spine of the Holy Land, this shard is meant to remind me to avoid temptation. A nearly identical piece of stone from Israel sits among my teaching trinkets. One of my students went to Israel back in my days at Nashotah House and returned with a bit of limestone for me. She said, “you can keep it as long as you put it on top of my gravestone when I die.” This was a custom I’d observed long before I’d even heard of Nashotah House. Long before religion grew flinty and unyielding. Stones bear remembrance. Although Israel is not as arid as many people believe it to be, rock is a natural resource of uncommon abundance. We age and die, but the rock remains. The rock remembers.

My six weeks in Israel were spent among the rocks of an ancient settlement known as Tel Dor. Archaeology, I learned, is mostly just removing the dirt from the rocks in the ground—at least at the entry level. Those stones tell a story. They were once a city, a district administrative center. Now they lie in dusty profusion, and only the most ardent of Bible readers will recall ever seeing Dor’s name in the pages of Holy Writ. Built by Solomon, the Bible grandly claims. Now all is ruins. The grandeur of a king toppled with the passage of time. My mind is drawn back to a treeless stretch of a mountain devoid of even the hardiest plants. A person can grow mighty hungry there. Mighty hungry indeed. Temptation comes, unbidden. Life is an unbroken chain of temptation, for those willing to be honest in the desert. That little stone is, in truth, bread.