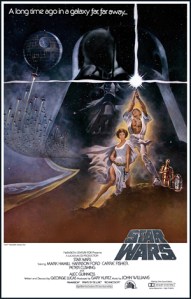

Maybe, if you’re like me, you find the Star Wars franchise a little hard to keep straight. Ever since the end of Episode VI the number of characters with strange and oddly short names jumped. The rate of light saber duals skyrocketed, and the story grew more complex (and not always with any payoff). I suspect that like many I kept watching the second trilogy of episodes I through III out of a sense of duty, longing for that pathos that stayed with me after leaving the theater (remember theaters?) following episodes IV through VI. Hope awakened along with the Force in Episode VII under the able hand of J. J. Abrams. Then the stinker of Episode VIII, which my wife and I watched in a cold theater in Bernardsville, New Jersey, dropped us back into the realm of I through III. I didn’t even notice when Episode IX, The Rise of Skywalker came out last year. DisneyPlus, to which many people subscribed just to watch Hamilton, made it possible for us to round out the trilogy of trilogies on the small screen.

While better than The Last Jedi, the story ran into the standard sequel problems of probing relationships between characters that a crisp story tends to leave ambiguous. But there were, to my religious eye, many themes that seemed quite Christian. There was buzz when Kylo Ren’s cruciform light saber appeared in The Force Awakens, but the Christian tropes were more obvious as the series wound down. Rey, for example, finds out about the wayfinder from the first physical book of the series. It’s old and leather-bound and iconic. This is a kind of Bible. Jedis are shown to be increasingly messianic, and I thought having a female messiah was a nice touch. I was going to write “as the series closed,” but with the money made there’s little doubt that more will come from a galaxy far, far away.

Rey’s impressive Jedi feats look like miracles and her ability to raise the dead (or dying) and to heal in a time of an evil empire (for ancient Christians, Rome) rings familiar to those with Bible radar. The name Skywalker should’ve been a clue from the beginning (as it was for those of us who crowded the theaters in 1977), and the final shot of Rey on Tatooine where the setting of the binary stars make a halo around her head should eliminate any doubt. There are many throwbacks to the original trilogy in this final installment, and although the plot was more complex than necessary, it leaves the armchair theologian in a nice place. But some of us will always think of the holy grail as that found back when the evil in our own empire seemed, if briefly, to be waning.