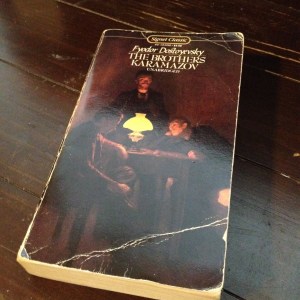

My experience of paternal parents growing up never led me to think Father’s Day was a holiday particularly worth celebrating. (Don’t panic—today’s not Father’s Day!) I do have an ironical sense of humor about the commemoration, though. So the other day when I clicked through one of Amazon’s many daily ads to my email account, I noticed it was for Father’s Day gifts. The first item listed was Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. Probably based on my browsing history, I thought. But no, I’ve been looking at non-fiction lately and I bought my well-worn copy of Dostoyevsky before Amazon was a gigabyte in Jeff Bezos’ eye, back when I was in seminary. Then it dawned on me: this is perhaps the most famous patricide novel ever written. Had the Amazon advertisers really thought about what they were recommending? “Here, Dad. It’s a book about sons killing their father.” If marketing is driving America, it may be time to pull over at a rest stop for a coffee break. Or at least read the book first.

I don’t pay attention to when Father’s Day is. It comes somewhere in that complex of spring holidays that include Passover, Easter, Mother’s Day, and Memorial Day. When my father was alive I sent him a card. It was a card to a stranger, but as Episcopalians know, it’s the done thing. I loved him, but I didn’t know him. Not that I’ve been a parent that deserves a holiday dedicated to my skill either. I confess my fair share of parental failures. They play and replay in my head, in the way the Protestant brain can never quite clear itself of guilt. We, as people, I believe, generally try our best to be good parents. It can be difficult, though. Nothing really prepares you for it.

One of my brothers once told me that, after having a girlfriend with kids from a previous marriage, he better understood how our stepfather viewed us as inherited children. Although I always want to claim the victim role in that scenario (I was only ten, what could I do?, etc.) his insight has stayed with me. It can’t be easy to inherit someone else’s progeny. It’s tricky raising your own child—that new person you want never to experience your own disappointments in life. Even cynics can be sentimental. But then again, I’ve been plowing through The Brothers Karamazov again since January, frequently laying it aside for weeks at a time. It’s not the kind of book I’d give a father on the edge. It’s okay, I think I’m good to drive again. I just won’t pay any attention to the ads I see beside the road.