I was recently asked to speak to a senior seminar about Holy Horror (many thanks for the invite!). One of the questions asked was how/why I chose the movies I did. The same question applies to Nightmares with the Bible. The thing is, my avocation is an expensive one, particularly on an editor’s salary. The number of horror movies is vast and our time on this planet is limited, so one thing any researcher has to do is draw limits. Otherwise you get a never-ending project (some dissertations go that way). I had figured, for both books, that I’d seen enough movies to make the point I was trying to make. Neither book was intended to be “the last word,” or comprehensive, but were attempts to open the conversation. Since none of my books have earned back nearly what resources I’ve put into them, a line has to be drawn. Movies are expensive when they get to the bottom of the “outgoes” column.

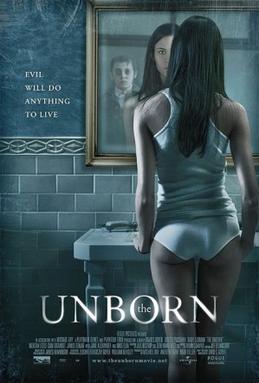

All of this is to explain why I didn’t include The Unborn in either book. (It fits into both.) I was aware of the movie, but I had to decide what I could afford in order to get the books written. I confess that I wish I’d watched this one sooner. (Remember, it’s a conversation!) This movie has so much in it that I may break my self-imposed rule of no double-dipping for blog topics. Or perhaps I’ll pitch something to Horror Homeroom. The Unborn is about a dybbuk. Like The Possession, it features a Jewish exorcism. Like An American Haunting, a holy book is destroyed. (The credits include a statement that no actual Torahs were harmed in the making of the film.) Interestingly, the exorcism is a joint effort between a rabbi and an Episcopal priest. Held in an asylum. It’s also a story about twins.

The skinny: college-aged Casey is being pursued by a three-generation dybbuk. Her mother, who died by suicide in an asylum, had been adopted. Casey is unaware that she was a twin, her brother having died in utero. She discovers her birth grandmother, a Holocaust survivor, who clues her in to why all the strange things are happening to her. Her own twin brother was possessed by a dybbuk at Auschwitz. It is now after Casey, having caused her mother’s suicide. The plot is pretty sprawling, and the exorcism scene over-the-top, but I’m only scratching the surface here. There’s so much to unpack that I wish I had a bigger movie-and-book budget. But then we all have our demons with which to struggle.