The existentialists, remember, used to put scenes in their plays to remind you that you were indeed watching a play. In keeping with their philosophy, there was no reason to fool yourself. Meanwhile, movies seldom break the fourth wall, immersing you in a story that, if done right, will keep your eyes firmly on the screen. With home based media, however, we’ve all become existentialists. (Of course, some of us had made that move before the internet even began.) When we watch movies we always have that “pause” button nearby in case an important call, text, or tweet comes through. We can always rejoin it later. Life has become so fractured, so busy, that an unbroken two hours is a rarity. I see the time-stamps on my boss’s emails.

While the existentialist side of me wants to nod approvingly, another part of me says we’ve lost something. What does it mean to immerse ourselves into a story? I know that when I put a book down it feels like unraveling threads at the site of a fresh tear in the fabric of consciousness. Even the short story often has to be finished in pieces. Poe, who knew much, wrote that short stories should be read in a single sitting. All of mine have bookmarks tucked into them. For a fiction-writer-wannabe like me, you need to feed the furnace. To write short stories, you have to read short stories. Novels must be spread over several weeks. Some can take months. I would like long novels again if time weren’t so short. Presses are even encouraging authors to write short books. Readers want things in snippets.

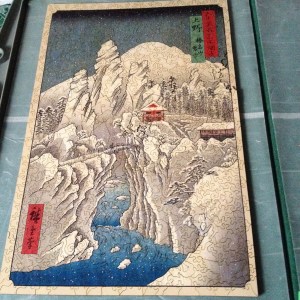

Perhaps all this fragmentation is why I enjoy jigsaw puzzles so much. Part of the thrill is remembering several places in the picture simultaneously. Being able to pick up where you left off. I limit my puzzle work to the period of the holidays when I can take more than one day off work in a row and the lawn doesn’t require attention and those trees that you just can’t seem to get rid of don’t require monitoring. But puzzles are designed for interruption. Movies and short stories are intended to engage you for a limited, unbroken period. The real problem is that we’ve allowed our time to become so fragmented. A creative life will always leave several things undone by its very nature. Other forces, mostly economic, will demand more and more time. The best response, it seems to me, is to be existentialist about it.