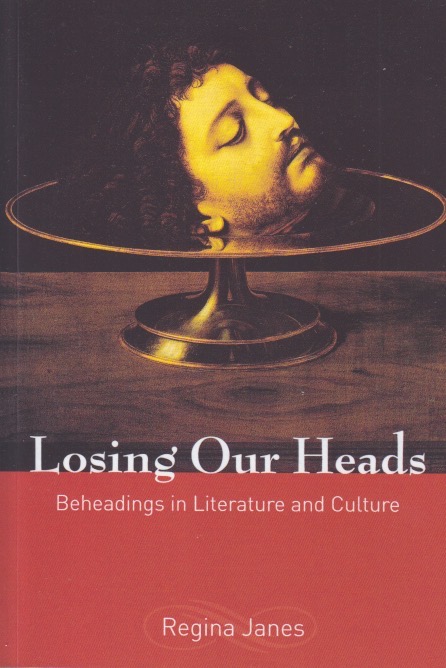

“Heads, I win,” is common enough as a call for flipping a coin. That element of chance plays through Regina Janes’ Losing Our Heads: Beheadings in Literature and Culture. You see, John the Baptist has a lasting place among the beheaded—indeed he’s featured on the cover of the book. And since Janes is looking at the topic in literature and culture, you can’t very well leave John out. I wonder what it says about humanity that there are so many other possible examples to include that this book is a mere sampler. Applying literary theory to the process, it becomes, well, theoretical at points, but still it’s an eye-opening book. Even if not always comfortable to read. The first few chapters, which cover the development of European beheadings, aren’t sweetness and light. There’s more happening here than meets the eye. These heinous acts set the stage for symbolism, however.

The material on John the Baptist is fascinating and insightful. It’s ironic, in some ways, that Jesus’ cousin is perhaps most famous for being beheaded. He also sheds light on his more famous family member through literary parallels. And, of course, it doesn’t end there. The idea gets picked up and explored by others in various art forms. You don’t really want to look, but since they’re there in the illustrations, you do. Then the book moves on to African stories. Playing off Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Janes gives voice to African authors who explore beheading within their own cultural contexts. All this goes back, historically, much further than John. Indeed, beheading is part of very early myths as well. It does make you stop and think.

I read books like this looking for clues. There’s a larger object in mind. And some of the insights I found were in examples afforded only a paragraph here or there. I read this book because of a journey of which a colleague sent me through an innocent enough discussion. There’s a reason we talk of excitement as “losing our heads,” and for some of us that excitement is research-laden. Naturally squeamish, I’m an odd one for watching horror. There’s something more to find here, however. Although gruesome at points, you learn something from wandering through this museum of heads. And when looked at through different lenses (of course, Freud is there) new perspectives emerge. Beheading is violent and yet it’s been a part of human culture for a very long time. There’s much to ponder here.