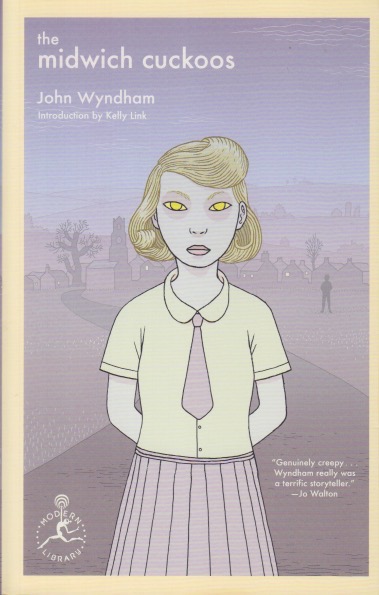

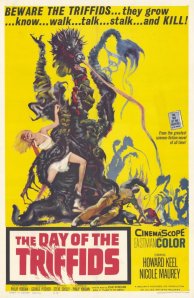

John Wyndham is someone I discovered through movies. Often considered a science-fiction writer, his works cross over into horror, particularly on the silver screen. Many years ago I read Day of the Triffids and, having seen Village of the Damned, wanted to read The Midwich Cuckoos. It was a pretty long wait. I kept thinking I might find a copy in a used bookstore, but it never happened. When I saw a reprint edition I ordered it with some Christmas money. There are some horror and sci-fi elements to the story, but there’s also a bit of thriller, as it’s called now, thrown in. The book is quite philosophical because of the character Gordon Zellaby, a Midwich resident who keeps thinking about what is happening in terms that don’t match the expectations of other, more prosaic thinkers. In case you’re not familiar:

Midwich becomes unapproachable for a period because an alien ship (the sci-fi part) has covered it. Everyone in the village is asleep for a couple of days. When they awake, generally no worse for wear, they soon discover that all the women of childbearing years are pregnant. They all give birth about the same time to children that look eerily alike and have bright golden eyes. The officials know this has happened but adopt a wait-and-see attitude. Meanwhile, the locals get on with things but they discover these new children develop about twice as quickly as humans do and they can control people with their minds. They also have collective minds so that their brainpower is quite above that of Homo sapiens. Zellaby makes the connection with cuckoos—birds that lay their eggs in the nests of other birds and after they hatch shove the other chicks out of the nest. Indeed, this is a story about what if cuckoos were humanoid aliens who tried the same thing with people. Told with a British stiff upper lip.

The story slowly unfolds and gets scary as it grows. I saw the movie quite a few years ago and the details were lost on me, so I was learning as I read. I suspect that it differs from the book quite a bit. Perhaps it’s the Britishisms that make this story less of a horror tale. There’s a kind of jocularity to the style, at least for a good bit of it. The serious issues of how governments and individuals interact is raised and discussed to a fair extent. Even though the book is fairly short, there’s a lot going on here. But now I need to watch the movie again.