The kaiju monster film has evolved significantly, as my post on Godzilla Minus One may indicate. Monster boomers grew up with Saturday afternoon kaiju, although we never heard that word. (Or at least I didn’t.) Godzilla was the most famous, but some people trace the origins of the idea to King Kong. The kaiju, or “strange beast,” genre features outsized monsters that, when they come in contact with civilization, wreak havoc. Many are primarily symbols of atomic fear, and after watching Godzilla again, I settled down one uncomfortably hot summer afternoon to watch Monster from a Prehistoric Planet, a wildly misleading title for a movie also called Gappa, which is more accurate but less eye-catching. A gappa is a “triphibian beast” that does equally well on land, water, or in the air. I do have to wonder if Michael Crichton saw this film before coming up with the idea for Jurassic Park.

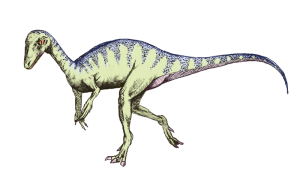

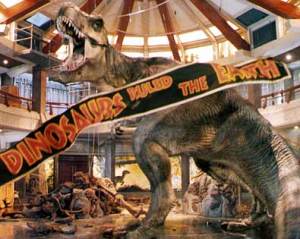

A wealthy publisher wants to open a tropical island resort in Japan. (You see?) He wants to fill it with exotic animals, and among those in the model are dinosaurs. His expedition to collect specimens leads a Japanese crew to discover a newly hatched gappa, which they take back to Japan. (The publisher, concerned that their find has been exaggerated, utters the title of this post.) Meanwhile, back on Obelisk Island, the gappa parents return and aren’t pleased to find their baby gone. They head to Japan to stomp around, Godzilla style. It takes the sole survivor from Obelisk Island, a young boy, to figure out that the parents really only want their baby back. The publisher, scientist, and journalist (all male) don’t want to give it up. The female lead, also a journalist, convinces them that they must. Japan is saved.

Kaiju have more recently become somewhat believable, and even a bit scary. The monsters themselves seem to be metaphors. It’s no accident that these early movies, such as Gappa, expend much of their screen time on explosions. From the artificial volcano on Obelisk Island to the model tanks and missiles, to the plumes rising as the gappa lead to destruction, things are always blowing up. The Japanese think at first that “Gappa” is a god, but the local boy who survives is emphatic that “Gappa” is “no god.” Yet the locals are careful not to raise their wrath. These movies aren’t great in any traditional sense, but they are imbued with reminders of war—no god—and the lasting damage it causes. And the wealthy can lead to the destruction of many cities for the sake of making money off of a stupid burnt lizard.