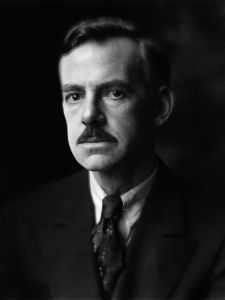

Those who write put part of themselves into every piece. Sometimes that tiny fragment of the author is nearly invisible, while at other times fiction becomes difficult to separate from biography. One of my daughter’s assigned summer readings is Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night. Since I use the opportunity of her assigned readings to catch up on what I should’ve read long ago, I recently sat down to see what the play was about. A dysfunctional family. Alcoholism, tuberculosis, and self-loathing are the unholy trinity of much writing from the nineteenth and turn of the twentieth centuries. But God also comes into the mix. Perhaps the divine was nearer to the surface back in the days when you might assume every other American had been raised in a Christian household. O’Neill’s dark and disturbing Tyrone family might be considered good candidates for irreligion were it not for the fact that being Catholic was so much a part of Irish identity in those days. Perhaps in some quarters it still is.

Those who write put part of themselves into every piece. Sometimes that tiny fragment of the author is nearly invisible, while at other times fiction becomes difficult to separate from biography. One of my daughter’s assigned summer readings is Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night. Since I use the opportunity of her assigned readings to catch up on what I should’ve read long ago, I recently sat down to see what the play was about. A dysfunctional family. Alcoholism, tuberculosis, and self-loathing are the unholy trinity of much writing from the nineteenth and turn of the twentieth centuries. But God also comes into the mix. Perhaps the divine was nearer to the surface back in the days when you might assume every other American had been raised in a Christian household. O’Neill’s dark and disturbing Tyrone family might be considered good candidates for irreligion were it not for the fact that being Catholic was so much a part of Irish identity in those days. Perhaps in some quarters it still is.

In Act Two, Scene Two James Tyrone is discussing his wife’s as yet unrevealed addiction with his two sons. Edmund, the scholar (and in reality bearing the family position of O’Neill himself), has rejected belief in God. He asks his father if he prayed for Mary in the days when her difficulties began. “I did. I’ve prayed to God these many years for her,” James Tyrone declares. Edmund responds, “Then Nietzsche must be right.” The debate is the classic issue of theodicy—where is God when things go wrong? Mary, the wife/mother believes she was bound for a convent, having been raised in Catholic school. When her life spirals in unexpected directions, she chooses morphine over faith in God, and the men, soused in whiskey, wonder who’s to blame. James, the father, declares atheism to be the culprit.

I found this an interesting study. Characters either unthinkingly accept the religion with which they were raised, or reject religion altogether. Edmund follows up his declaration by quoting Thus Spake Zarathustra: “God is dead: of His pity for man hath God died.” Nietzsche is never simple to comprehend, but even in the declaration of the divine death is an implicit indication of the existence of deity. The subtle nuances here are often lost in family debates where God’s abstract existence is far less important than the human suffering that raises the question in the first place. O’Neill was writing not only in the shadow of Nietzsche, but also of Karl Marx and other theorists whose nails had been pounded into the heavenly coffin over the past two centuries. So Mary, in her morphine vision, returns at the end of the play to state, “I went to the shrine and prayed to the Blessed Virgin and found peace again because I knew she heard my prayer and would always love me and see no harm ever came to me so long as I never lost my faith in her.” The reader, however, along with Karl Marx, knows that this is really the opiate of the people finding voice through one of the faithful.