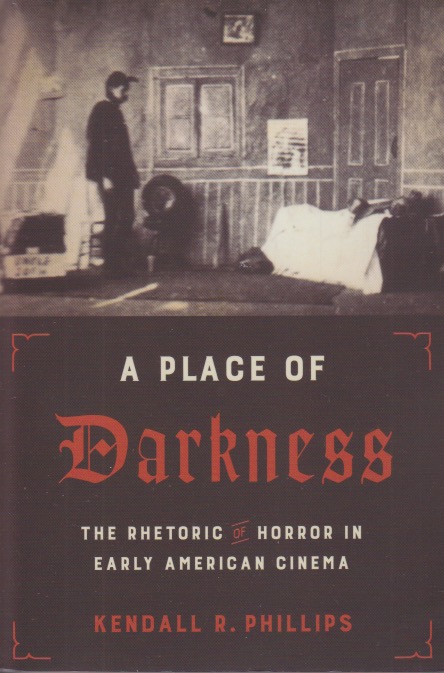

We’re spoiled. The intensity of our media experiences makes it nearly impossible to imagine the truth of stories that viewers fainted at films such as Frankenstein even less than a century ago. This change in outlook, this sense of being over-stimulated, occurred to me while reading Kendall R. Phillips’ excellent A Place of Darkness. In keeping with the subtitle (The Rhetoric of Horror in Early American Cinema) Phillips primarily addresses pre-Dracula films, beginning in 1896 and demonstrates how horror themes emerged early and evolved along with society’s norms. There is so much insight here that it’s difficult to know where to begin. For me one of the big takeaways was how Americans at this stage were eager to appear non-superstitious and how they used that concern to keep the supernatural out of early ghost films.

Phillips isn’t afraid to address the role of religion in horror. Other cultural historians note this as well, but many pass over it quickly, as if it’s an embarrassment. Since my own humble books in the field of horror are based on the religious aspects of such movies, I’m always glad to find specialists who are willing to discuss that angle. As America grew more and more enamored of the idea of rationalism, less and less energy was put into suggesting that anything supernatural might be at work. Supernatural was considered foreign and cinema followed society’s lead. This led to—and I want to add that this isn’t Phillips’ terminology—the Scooby-Doo Effect where every seeming monster had to be revealed as a hoax. As a kid I watched Scooby-Doo in the vain hope that the mystery might turn out to be real.

Studies of horror films generally acknowledge that the first real member of that genre is Tod Browning’s Dracula of 1931. Phillips demonstrates the valuable pre-history to that and does an excellent job of explaining why Dracula was such a singular movie. Horror elements had been around from the beginning, but Browning’s film made no excuses—the vampire is real. Audiences were shocked and thrilled by this and other studios didn’t quite know whether they should follow Universal’s Depression-Era success or not. Mostly they decided not to. The Universal monsters seem innocent enough today, but we go to theaters where the floors shake when heavy footsteps fall and the sound of a door creaking open comes from behind us. Special effects make the horror seem real. No excuse is made for religion and its monsters. We’re spoiled.