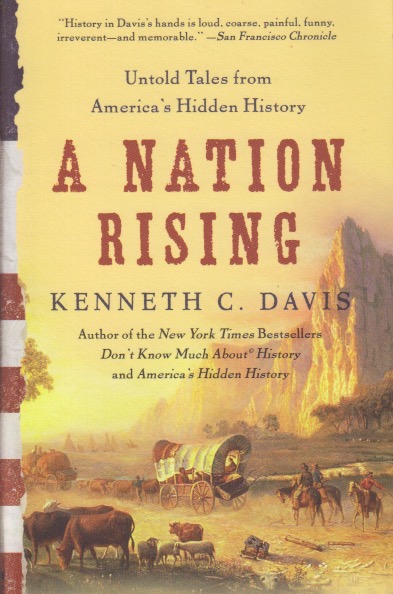

Perhaps because I was a critical thinker at a young age, or maybe because I’ve always been insistent on fairness, I never took an interest in American history. I cast my eyes back further, wondering how we got to where we are. Such looking backward would lead to my doctorate. Now, however, I’m interested. I’d pay better attention to American history in school, were I now required to attend. I’ve known about Kenneth C. Davis’ A Nation Rising since shortly after it was published. My family listened to part of the recorded version when long car trips were more common. Remembering what we’d heard, I eventually purchased the print book as well—I’m a fan of print and always will be, I’m afraid. I only resort to ebooks when there’s no other option.

In any case, what drew me to these Untold Tales from America’s Hidden History was the information about early revivals. Particularly those of George Whitefield. Now, I’d learned about Whitefield in seminary (it was in United Methodist history, as it happens), but I hadn’t realized that he was America’s first superstar entertainer. People flocked to hear him preach and he even caught the attention and friendship of Benjamin Franklin. It’s estimated that Whitefield reached an audience of about 10 million hearers, and this was back in the eighteenth century. He also preached in England and since the American population was just over 2 million in those days, it means he was enormously popular over here. It was Davis’ book, not a seminary class, that made me aware of the fact.

Having grown up in one of the original thirteen colonies—Pennsylvania was a state by then; I’m not that old—you’d think I might’ve been more interested. George Washington was in western Pennsylvania at least a time or two, and I even found a Civil War coat button poking out of the ground in our backyard once. Nevertheless, it took adulthood, and perhaps the recognition of just how fragile our democracy is, to kickstart my interest. Davis’ book is good for those who are interested in the lesser-known aspects of American heritage. We aren’t always the good guys, though. This isn’t the heavy-duty history that totters with facts and figures. Really, it’s a set of fascinating vignettes of many people mostly forgotten these days. And like most American histories, it shows that our political troubles today are nothing new.