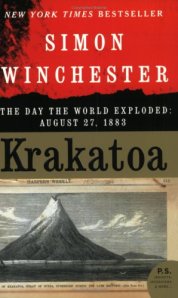

Just 200 years ago, there was a “year without a summer.” Well, that’s an exaggeration, but the name has stuck and is familiar to those of us with an undue interest in weather. Although the coldness of that summer was far from universal, frosts came in New England in June, July, and August, killing off the staple corn crop for much of the region. Snow fell even later than it usually does in the northeast, including a measurable fall in July. My interest in this particular cooling episode was spurned by reading about the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883. The connection? Mount Tambora, a relative neighbor of Krakatoa, erupted in 1815 with an ejected debris volume of about ten times that of its later colleague. The dust cloud from Tambora has long been a culprit for the dismal summer the following year. Henry and Elizabeth Stommel researched and wrote a little book on this event entitled, Volcano Weather: The Story of 1816, the Year Without a Summer. Although the book shows its age (it was written in the early 1980s), it remains a fascinating exploration of the many things that weather can do. And has done. Two of my favorites from this book were Napoleon’s adventures and the writing of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley during a rainy summer in Switzerland.

Just 200 years ago, there was a “year without a summer.” Well, that’s an exaggeration, but the name has stuck and is familiar to those of us with an undue interest in weather. Although the coldness of that summer was far from universal, frosts came in New England in June, July, and August, killing off the staple corn crop for much of the region. Snow fell even later than it usually does in the northeast, including a measurable fall in July. My interest in this particular cooling episode was spurned by reading about the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883. The connection? Mount Tambora, a relative neighbor of Krakatoa, erupted in 1815 with an ejected debris volume of about ten times that of its later colleague. The dust cloud from Tambora has long been a culprit for the dismal summer the following year. Henry and Elizabeth Stommel researched and wrote a little book on this event entitled, Volcano Weather: The Story of 1816, the Year Without a Summer. Although the book shows its age (it was written in the early 1980s), it remains a fascinating exploration of the many things that weather can do. And has done. Two of my favorites from this book were Napoleon’s adventures and the writing of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley during a rainy summer in Switzerland.

I should note, however, that the Stommels do not declare that Tambora was the reason for the year without a summer. They tend to think the volcano had something to do with it, but the weather, that most protean of phenomena, can be impacted by the very small as well as the very large. In fact, their description of the eruption includes the recognition that locals felt volcanic eruptions to be normal acts of the gods. Many island cultures recognize the divine power of the molten earth. The weather getting out of whack, we can be sure, leads to much prayer even today, thousands of miles from any eruption. Something that hasn’t changed since the 1980s is that natural phenomena—especially powerful ones—evoke the divine. Huge, impressive volcanoes, or even the very immensity and complexity of the atmosphere, suggest something we can’t comprehend. Global warming will soon, however, bring this point home.

One of my takeaways from this book is the fact that the weather’s lack of uniformity emphasizes just how little we know. The year without a summer mainly affected the northern hemisphere, and that only piecemeal. Parts of northern Europe and North America felt it more intensely than other places. It was not “the coldest year ever” and anyhow, is it even possible to know whether the coldest year would feel unnecessarily chilly where you are? I’m pretty sure it’s snowing in some part of the world right now. Human arrogance when it comes to global warming can be put into perspective by such acts of nature as Tambora. From a human perspective, we live on a time bomb. Volcanoes care not a whit for our bidding and wishes and dreams. They can impact climate more instantly than our trite human efforts and thinking we alone are gods. To prepare for the future sometimes we need to look two centuries back.