I’m never quite sure how I’m supposed to approach books of short stories. Some of them are truly massive and contain only a handful of tales I wish to read. Others are governed by a dedication to the author that compels me to read from cover to cover. Some are by differing authors, among whom some appeal more than others. I wasn’t sure where to begin with Jorge Luis Borges. Not having been raised in a literary family, and having never formally studied literature, I found Borges through a friend and co-worker. After my academic career crashed and burned, I started reading more literary writers and discovered Borges again and again. I knew the basics of his story—he was perhaps the most famous Argentine writer, he had gone blind, and he had written probing, unusual stories.

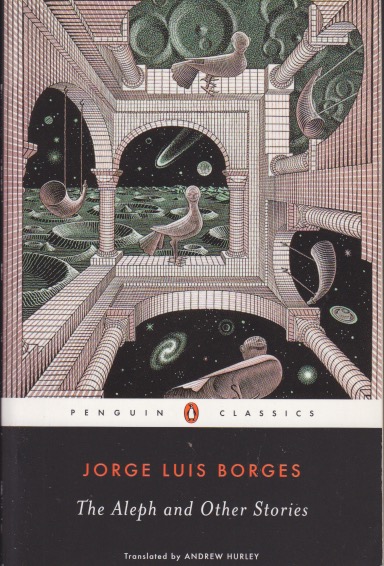

I picked up this collection because of the title. “The Aleph” is included here. It was also the title of a collection of Borges’ stories, which make up the basis of this book. To that collection are added some other pieces, and these last become a mix of poetry and philosophy more than a simple narrative. Of course, Borges didn’t write simple narratives. His stories are layered labyrinths. A complex person doesn’t write simple stories. Often they reflect on religion. Some of them explicitly so. They aren’t, however, religious stories. Indeed, I was drawn to “The Aleph” because of my own experience of Hebrew and the sense that it is a sacred language. Borges also puts this into the mix here.

So what kind of collection is this? I’m still not certain. This time I did read it cover to cover and at several places I became uncomfortable. Borges doesn’t shy away from the harsh realities of life. What people are capable of doing to each other, and what they in fact do. Some of the pieces just under a page long stopped me in my metaphorical tracks. Was I reading fiction or some kind of history? Was philosophy secretly being fed to me by being left right out in the open? This isn’t weird fiction, although it’s clear that some of it could be taken that way. It is the work of a mind that operated on a plane different from that of many others. There’s an uncertainty, a tentativeness here that is very becoming, and even beguiling. Having read the book I’m not sure what it was. It will, however, lead to yet more reading. Of this I am certain.